With Japan taking on an increasingly strategic role in ASEAN’s smart city financing, combining investment support with technical expertise, this article explores the key criteria and practical pathways cities can adopt to secure Japanese capital.

As of September 2024, the ASEAN Smart Cities Network (ASCN) has recorded 108 active smart city projects across the region. These initiatives cover six key focus areas: civic and social services, quality environment, built infrastructure, industry and innovation, safety and security, and health and well-being.

Smart city development in ASEAN is expected to continue expanding alongside the region’s rapid urbanization, with the urban population projected to rise from approximately 350 million today to nearly 405 million by 2030, representing around 56 percent of the region’s total population. This growth will place increasing pressure on infrastructure, mobility, energy systems, public services, and the environment.

Smart city initiatives are expected to play a crucial role in addressing these challenges by integrating technology-driven solutions across sectors such as healthcare, education, transport, housing, and public services. The goal is not only to enhance quality of life but also to drive sustainable economic growth and strengthen regional competitiveness.

Financing opportunities for smart city projects in ASEAN are increasing, yet investment readiness remains a significant barrier. Funding is available through public budgets, bilateral and multilateral programs, and private sector participation.

Despite this growing pool of funding, many smart city proposals fail to attract investment. Beyond regulatory and governance challenges, the main barriers include insufficient data, weak feasibility assessments, and misalignment with investor expectations. Many initiatives present compelling visions but fail to provide the economic, social, and technical justification required to demonstrate true viability.

Moreover, project developers often fail to align with investor expectations—such as return potential, risk structure, and the tangible value a project will deliver. Without alignment to these criteria, even well-intentioned projects struggle to gain investor confidence and fail to progress beyond the conceptual stage.

Japan’s commitment to smart city development in ASEAN has progressed from offering technical advice to actively sharing end-to-end project expertise. Through initiatives such as the Japan-ASEAN Smart Cities Network (JASCA) and Smart JAMP, Japan supports cities not only with best practices and knowledge exchange but also across the entire project lifecycle—from feasibility studies and planning to implementation guidance. This collaborative approach ensures that solutions are context-specific, practical, and aligned with local development needs.

Beyond knowledge support, Japan is now playing a direct investment role in smart city initiatives across the region. The Japanese government has committed ¥250 billion (approximately USD 2.4 billion) to support Japanese companies to participate in smart city projects in Southeast Asia.

This financing includes ¥50 billion (USD 483.5 million) from the Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport and Urban Development (JOIN) and ¥200 billion (USD 1.9 billion) from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC). By combining financial backing with technical partnership, Japan is positioning itself as both a knowledge leader and a strategic investor in ASEAN’s urban transformation.

Investors assess the broader ecosystem and economic foundations of a city before committing capital. Two recurring success factors consistently shape investor confidence: Sustainability as an Economic Engine and Digital Evolution as a Growth Catalyst.

Many emerging smart city developments have struggled over time because they focus on livability, housing, or aesthetics without establishing the economic engine needed for long-term growth. For a smart city to be viable, sustainability must operate as an integrated ecosystem—one that improves quality of life while actively supporting economic activity. This includes creating conditions where businesses can invest, operate, and expand, supported by enabling infrastructure, sound regulation, and accessible markets. In short, a city becomes attractive to investors when it combines social well-being with economic scalability.

Digital evolution plays a critical role in signaling future readiness. Cities that leverage digital transformation as a growth driver are better positioned to attract capital. This typically begins with a shift from “heavy to light,” where traditional physical infrastructure is reduced or replaced through solutions such as digital twins, smart street lighting, or IoT-based systems. As these digital layers expand, the development cycle eventually shifts “from light back to heavy,” prompting new investments in infrastructure like data centers, 5G networks, and advanced connectivity. Cities that can manage both phases show adaptability, resilience, and long-term scalability—qualities that significantly increase investor confidence.

Japanese companies follow a clear investment philosophy when making decisions about smart city development. Beyond the pursuit of attractive economic returns, IGPI, a Japan-based investment firm, anchors its approach on two core principles: citizen-centricity and value creation.

Japanese companies, including IGPI, prioritize smart city initiatives that respond to real community needs rather than being driven solely by technological trends. Technology is viewed as an enabler to create tangible value and improve citizens’ quality of life.

The focus is on solving pressing urban challenges such as congestion, housing, mobility, public health, education, and access to essential services. A project is considered “smart” only when it delivers visible and measurable improvements that citizens can experience, adopt, and benefit from in their daily lives.

In line with the broader Japanese investment philosophy in ASEAN smart cities, IGPI considers a project investable only when it offers opportunities to add value beyond capital injection. Rather than acting solely as a financier, IGPI seeks opportunities where its involvement can influence strategy, strengthen implementation, and improve the overall viability of the project.

Equally important, IGPI looks for opportunities to bring in Japanese strengths—such as advanced technologies, operational expertise, and private-sector partners—to support delivery and long-term sustainability. The focus is on contributing capabilities, know-how, and networks that elevate both the quality and bankability of a smart city initiative.

To attract investment—particularly from Japanese investors—cities must rethink how they design, frame, and communicate their smart city initiatives.

This begins with a clear vision and a clearly defined problem to solve.

A city’s vision must be more than aspirational language. It should align with social, economic, and environmental priorities while also reflecting investor expectations. The vision needs to articulate tangible benefits for both citizens and businesses, rather than presenting broad or abstract ambitions that are difficult to operationalize or measure.

In addition, smart city projects gain traction when they address specific, well-scoped challenges—such as mobility, waste management, energy efficiency, or public service delivery. A targeted problem makes it easier to quantify outcomes, assess impact, and present a credible investment case. Investors are more confident when they can clearly evaluate expected returns, risks, and measurable benefits.

In short, ASEAN cities that link vision with evidence-backed execution can unlock Japanese investment and accelerate their path toward sustainable, smart urban transformation.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Febrizal, Associate of IGPI Singapore

Prior to joining IGPI, Febrizal worked at YCP Solidiance and PwC Indonesia, where he successfully completed a range of consulting projects, including market entry strategy, growth strategy, and business model identification, across diverse industries such as Agriculture, Automotive, and Industrial. He has extensive experience in M&A activities, including conducting commercial due diligence, valuations, and providing deal advisory services (connecting buy-side and sell-side). Febrizal holds a degree in Economics from Binus University.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit and Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Few countries possess the depth of experience that Japan has in areas now central to Singapore’s construction agenda. Off-site modular construction, robotics for site automation, seismic-resilient structures, and next-generation building materials are all domains where Japanese firms excel. These capabilities are highly relevant as Singapore pushes for higher productivity, faster project timelines, and more greener outcomes.

Opportunities are also emerging in zero-energy buildings, water-sensitive urban design, and smart infrastructure systems. Japan’s experience with integrated urban planning and clean, efficient design positions its firms to deliver solutions that go beyond compliance, offering strategic ESG value to both government and private sector clients.

The shift toward sustainable and ESG-oriented construction in Singapore creates an additional pathway. Japanese companies that offer integrated consulting services which combines engineering expertise with green building solutions are well placed to capture demand in design, operations, and lifecycle management.

Beyond the familiar sectors, there are niches where Japanese capabilities offer unique value. Construction waste management is gaining urgency in Singapore, where buildings are often demolished and rebuilt on rapid cycles. Japan’s leadership in waste reduction, recycling, and process discipline offers a roadmap for more circular practices.

Likewise, Japan’s unparalleled expertise in disaster detection and early warning systems can support Singapore’s climate adaptation agenda. Technologies developed for earthquake-prone rail systems, such as Japan’s high-speed sensor networks, could be adapted to coastal protection or critical infrastructure management in the region.

These are not just technical exports. They are operational philosophies rooted in a culture of foresight, systems thinking, and preparedness, which are qualities increasingly essential in a world of cascading risks.

Singapore remains highly receptive to foreign construction solutions, especially when they serve national imperatives in safety, sustainability, and efficiency. However, openness does not guarantee success. Japanese firms must localise their offerings technically, operationally, and commercially.

Solutions must adapt to tropical climates, local building codes, and highly competitive pricing environments. Japanese companies, often optimised for high-spec domestic delivery, must re-engineer their models for cost-conscious, value-driven markets.

Equally important is the ability to engage early with regulators, developers, and project owners. Many Singaporean agencies now manage project planning in-house. Success requires presence from the concept and ideation stage, not only at the tender phase.

Japanese companies enjoy strong reputations in Singapore for reliability, precision, and technical integrity. These qualities resonate with both public and private stakeholders. Yet reputation alone does not secure contracts.

Speed, transparency, and cultural flexibility are increasingly essential. This includes responsiveness to project timelines, openness in partnerships, and the ability to tailor offerings to specific market needs.

Demonstration matters. Firms that have established innovation labs, run pilot projects, or co-developed solutions with local stakeholders have seen greater success. Market visibility builds credibility especially in a market where decision-making is fast-paced and data-driven.

The most effective market strategies involve collaboration. Joint ventures, strategic alliances, and public-private consortiums remain the preferred entry routes. Acquisitions of local players or strategic partnerships with engineering consultancies can offer immediate access to networks and pipelines.

But structure alone is not sufficient. Companies must show commitment through localisation, capability transfer, and long-term engagement. Those who do will find Singapore not just a market, but a regional platform for Southeast Asia’s construction sector.

Singapore’s influence extends well beyond its borders. It is a reference city for infrastructure development across Southeast Asia, and increasingly, a global showcase for smart, sustainable urbanism. To succeed here is to demonstrate global leadership.

The moment is opportune. Singapore is positioning itself as a next-generation construction hub in Asia. Its openness to innovation, pro-business policies, and scale of ambition make it a rare environment for experimentation and growth.

Japanese firms with their unmatched technical DNA are uniquely placed to shape this future. But doing so requires more than exporting excellence. It will require embedding themselves in the ecosystem, adapting to its pace, and building trust at every level.

Singapore does not need more suppliers. It needs co-creators in construction and urban innovation. The Japanese companies that recognise this and act boldly will not only thrive in Singapore. They will help define what the global construction sector looks like in the decades to come.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

The newly envisioned Johor–Singapore Special Economic Zone (JS-SEZ) offers a real-world laboratory for addressing these gaps. But for this model to become a prototype for broader integration, foreign investors must recalibrate expectations, and policymakers must confront structural bottlenecks head-on.

ASEAN’s charm lies in its diversity—but so do its challenges. While the bloc has made commendable strides in reducing tariffs and building cross-border manufacturing networks, it remains far from a unified economic system. Labor mobility is limited. Regulatory frameworks vary significantly. Legal interpretations shift not only by country but also by jurisdiction within countries.

The comparison with the European Union is instructive. EU economies may differ in size and character, but their integration is underpinned by harmonized legal structures, mutual recognition of standards, and enforceable treaties. ASEAN, by contrast, functions more like a patchwork of bilateral understandings, informal cooperation, and inconsistent rulebooks.

For companies hoping to plug into regional supply chains or scale seamlessly across borders, this means facing an operational maze, from incompatible logistics regulations to shipping restrictions and bureaucratic red tape.

Perhaps the most insidious challenge is one of legal unpredictability. In many ASEAN jurisdictions, the rule of law exists—but the ability to predict how it will be interpreted or enforced often does not. This uncertainty, while manageable for domestic entrepreneurs used to navigating grey zones, becomes a deal-breaker for boards in Tokyo, Frankfurt, or New York.

When corporate investment decisions hinge on long-term capital deployment and regulatory stability, ambiguity is expensive. For new economic zones such as JS-SEZ to attract serious foreign capital, they must offer more than incentives—they must deliver regulatory clarity and enforcement consistency.

Even partial legal insulation within designated industrial corridors or digital zones, could significantly enhance investor confidence.

Japan’s development model offers lessons for ASEAN. Postwar industrialization in Japan did not concentrate solely in Tokyo or Osaka. Through deliberate policy—led by agencies like METI—Japan nurtured industrial clusters nationwide, ensuring inclusive, regionally balanced growth.

Japanese companies, many of which were born from this distributed ecosystem, are uniquely suited to help ASEAN avoid the pitfalls of uneven development. They bring not only technological capability but also the operational discipline to build sustainable, long-term infrastructure in second-tier cities and overlooked geographies.

Moreover, Japan’s increasingly robust ESG posture makes its companies natural partners in addressing ASEAN’s social and environmental gaps—from labor protections to climate resilience. In this regard, Japan’s “soft power” of ethical business may prove more enduring than capital alone.

Amid escalating geopolitical rivalries, ASEAN offers something rare: neutrality. As global powers decouple and reconfigure trade alliances, Southeast Asia has emerged as a bridge—not a battleground. Its member states have deftly navigated competing pressures, signing trade pacts with the US while maintaining economic ties with China.

For Japanese firms, this geopolitical balance is not just a buffer—it’s a strategic asset. The JS-SEZ and similar corridors provide a platform to localize manufacturing, diversify suppliers, and serve regional markets—without choosing sides in great power competition. In an era of tariff shocks and regulatory unpredictability, this agility is worth its weight in gold.

To succeed in ASEAN, Japanese firms may need to rethink their own playbook. Rigid three-year business plans, while effective in stable environments, can become straitjackets in fluid, fast-evolving markets. Agility—both strategic and operational—must become core capabilities.

Rather than waiting for ideal conditions or attempting to deliver full-suite solutions from the outset, firms should lead with problem-solving. Enter with focused offerings that solve specific, localized pain points. Build trust. Prove value. Scale later.

This shift requires not just different tactics but a different mindset: from control to co-creation, from certainty to exploration. Regular on-the-ground research, agile partnerships, and culturally fluent teams will be essential in identifying the right entry windows and expansion triggers.

ASEAN’s integration journey will not mirror Europe’s—but that does not mean it is doomed to remain fragmented. With visionary public-private collaboration and sustained institutional reform, corridors like the Johor–Singapore SEZ can become blueprints for the region’s next chapter.

For Japanese companies—and their global peers—the road ahead is not without risk. But those who embrace ASEAN’s realities, invest in its capabilities, and help shape its institutions will not just participate in its growth. They will help define it.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

At the heart of the event was a compelling panel discussion moderated by a member of IGPI Singapore. The panel featured Mr. Marty Sinthavanarong, SVP, Head of International Business and Special Projects at Gulf Energy Development, and Mr. Angsutorn Wasusun (Jom), Director of the Bio-Circular-Green Economy Division at the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

The discussion centered on three interrelated themes – geopolitical shifts, sustainability imperatives, and Thai-Japanese collaboration – but it ultimately converged on one single message: In a world marked by uncertainty, Thai-Japanese partnerships grounded in co-creation, shared purpose, and long-term thinking are critical for building business resilience and driving sustainable growth.

The panel highlighted how shifting geopolitical dynamics, particularly escalating tensions among global powers – are reshaping corporate risk assessments and investment decisions. Companies are becoming increasingly cautious in politically sensitive markets, choosing instead to focus on regions offering greater long-term stability and neutrality.

Simultaneously, governments across ASEAN are accelerating efforts to deepen regional integration and diversify trade partnerships. By developing multilateral frameworks and strategic economic blueprints, countries in the region are working to buffer insulate themselves from external shocks while unlocking new intra-ASEAN and India-related business opportunities.

The panelists also emphasized the evolving role of sustainability in corporate strategy. Once viewed primarily as a regulatory requirement, sustainability is now a core driver of competitive advantage, stakeholder trust, and brand reputation.

Companies are actively pursuing long-term decarbonization goals through renewable energy investments, strategic acquisitions, and technology partnerships, with growing recognition that sustainability strategy must be authentic, context-specific, and internally driven.

Thailand’s public sector is creating a favorable environment for this transition. Policies such as the Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) Economy, Thailand 4.0, and the new National Energy Plan signal the government’s strong push toward green transformation. The Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) continues to be positioned as a leading hub for innovation, offering generous investment incentives for companies aligned with environmental and social goals.

Thai-Japanese business collaboration, with a history spanning decades, is now entering a new phase, defined not just by joint ventures, but by co-investment, co-development, and co-creation.

Japanese companies contribute technology expertise, precision, and long-term commitment while Thai companies bring agility, local market insight, and a strong willingness to innovate. Together, these complementary strengths are enabling meaningful progress in areas such as green hydrogen, infrastructure, and digital transformation.

Beyond individual projects, bilateral strategic action plans are reinforcing these efforts at a national level, with collaboration across human capital development, regulatory reform, and sustainability initiatives.

The dialogue reaffirmed a shared understanding: In today’s fragmented global landscape, collaboration built on trust, shared values, and mutual learning is the surest path forward.

Thai and Japanese enterprises, already closely aligned in culture and vision, are well positioned to lead ASEAN’s transition toward a more resilient and sustainable future.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

Harsh Munim, Associate of IGPI Singapore

Harsh is a dynamic professional with an MBA from NUS Business School and a BBA in Finance from City University of Hong Kong, where he also had the opportunity to go on an exchange program to Indiana University Bloomington in the United States. With over 4 years of experience, Harsh brings a wealth of expertise to his role at IGPI. Prior to joining IGPI, he worked as a Senior Project Manager at an investment research firm in Hong Kong, where he managed diverse projects in South East Asia and Oceania. During his MBA, Harsh interned with IGPI, contributing to projects related to carbon credits, microgrids, and the consumer goods industry. He also gained valuable experience at IQVIA, where he supported global pharmaceutical companies on LOE strategy, segmentation, targeting, and go-to-market projects.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Once a conceptual relic under frameworks like the SIJORI (Singapore-Johor-Riau Integration), the regional vision spanning Johor, Singapore, and parts of Indonesia has gained new relevance. The triggers are multiple and mutually reinforcing: the trade and tech tensions between the US and China, the recalibration of global value chains, and Asia’s rising centrality in demand and innovation. Add to this the surging cost of living and business operations in Singapore, and Johor’s appeal becomes self-evident—not as a competitor, but as a complementary force.

The JS-SEZ aims to remove longstanding friction in labor mobility, customs clearance, and cross-border collaboration. New infrastructure, such as the upcoming Rapid Transit System (RTS), QR code–based border processing, and special permits, is set to enable the seamless flow of talent and goods. This, combined with a business facilitation drive in Johor, creates an environment conducive to integrated operations spanning R&D, manufacturing, and services.

For Japanese and global firms, the opportunity is not simply cost arbitrage – It is architectural. Singapore continues to attract regional headquarters and high-value functions such as innovation and strategy. Johor, in contrast, can serve as the operational and manufacturing anchor, supported by more agile regulatory approvals and a younger labor pool.

The model is already visible in sectors such as data centers, where space and energy demands in Singapore have led firms to base more standardized, scalable functions in Johor while retaining high-end, latency-sensitive operations in the city-state. Similar paradigms are likely to evolve in logistics, digital services, and mid-to-high-tech manufacturing.

What sets this corridor apart is its ability to accommodate differentiated footprints. Firms can fine-tune their value chains across borders—high-touch client-facing services in Singapore, backend operations and prototyping in Johor, and increasingly, test-marketing and product validation in adjacent Southeast Asian locales.

The sectors poised to benefit most from this integration reflect the corridor’s comparative strengths. Financial services, advanced manufacturing, and digital infrastructure stand out. In each, operational decentralization is now not just viable—it’s desirable.

Pharmaceuticals and consumer technology firms may find particular advantage in combining Singapore’s robust R&D ecosystem with test marketing and light assembly in Johor. The zone effectively becomes a sandbox for adaptive innovation tailored to the region’s ten diverse markets.

Another compelling case lies in the automotive supply chain. With Southeast Asian OEMs like VinFast gaining ground, component manufacturers must rethink their traditional orientation toward global brands and instead design systems to serve regionally embedded demand—an area where Japanese manufacturing expertise could prove pivotal.

Japanese firms bring operational rigor and engineering excellence. Yet their traditional approach—self-contained, insular, and village-centric—may limit their potential in a cross-border ecosystem like JS-SEZ. The opportunity lies in two directions: partnering with local conglomerates who orchestrate the ecosystem, or transforming into system integrators themselves, blending architectural vision with operational execution.

The corridor offers Japanese suppliers a stage to serve both global and regional OEMs through localized innovation, agile manufacturing, and distributed logistics. Success will depend on their ability to step beyond the keiretsu model and embrace ecosystem-driven growth.

Despite its promise, the JS-SEZ will be tested by a familiar Southeast Asian challenge: talent. Johor’s ability to attract and retain skilled workers is constrained by the gravitational pull of higher wages in Singapore and better lifestyle options in Kuala Lumpur. While policy support and economic incentives may help, firms must invest in localized talent pipelines and rethink retention strategies to fully unlock the zone’s potential.

The Johor-Singapore SEZ is more than a logistical arrangement—it is a microcosm of the new regionalism. With digitized customs, interoperable regulatory systems, and tri-sector engagement (private, public, and multilateral), it could set a benchmark for other integration zones across Asia.

Firms that recognize its potential early—and align their footprints, partnerships, and supply chains accordingly—will gain a first-mover advantage. For strategy leaders, the message is clear: regionalization is not a fallback. It is the new frontier.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

However, this economic reliance on land transport comes at a steep environmental cost. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the transport sector accounts for approximately 30% of energy-related CO₂ emissions across Southeast Asia, with road vehicles responsible for nearly 90% of these emissions. This makes road transport not only a source of economic strength but also a primary contributor to the region’s carbon footprint.[1]

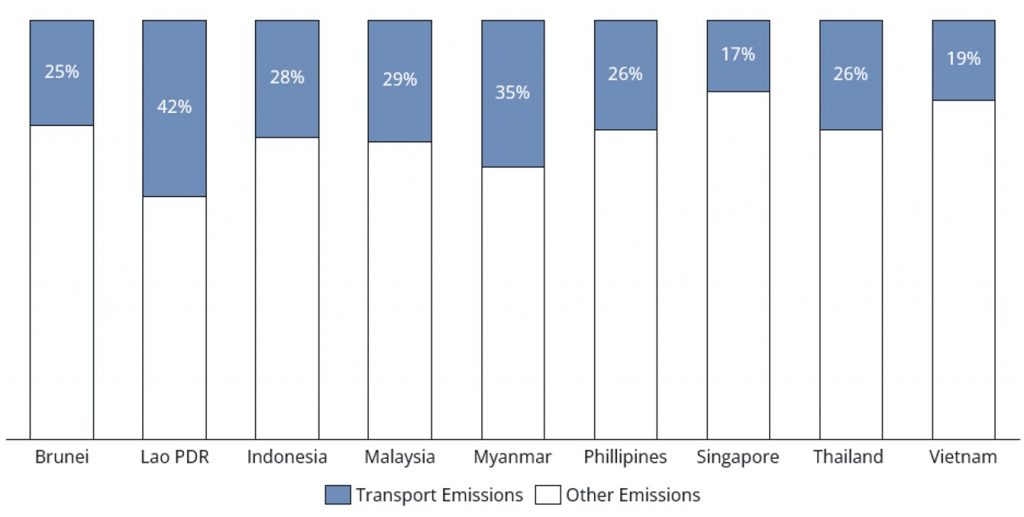

As ASEAN nations race toward their net-zero targets, one reality stands out: decarbonizing the transport sector is not just an environmental imperative – it’s a societal one. Road transport alone contributes disproportionately to national emissions. In 2023, the share of road transport in total greenhouse gas emissions ranged from 17% in Singapore to a staggering 42% in Lao PDR, with major economies such as Indonesia (28%), Malaysia (29%), Thailand (26%) and Philippines (26%) also bear a significant transport-driven emissions load.[1] This clearly signals that decarbonizing urban mobility must be a frontline priority – not a secondary concern.

Figure 1: Road Transport Emissions as share of total emissions in ASEAN 2023 [1]

But the case for transport decarbonization extends far beyond carbon reduction. It is also about saving lives. High concentrations of PM2.5 – a fine particulate pollutant largely caused by vehicle emissions – have silently reduced life expectancy across Southeast Asia. By permanently lowering PM2.5 levels from 2021 concentrations to the World Health Organization’s recommended guideline, countries can achieve extraordinary health gains. In Myanmar, such a reduction could increase life expectancy by 3 to 5 years. In parts of Laos and Thailand, a 2 to 3-year gain is possible. Decarbonizing transport is thus not only a climate mandate but also a public health intervention with tangible, measurable outcomes.[2]

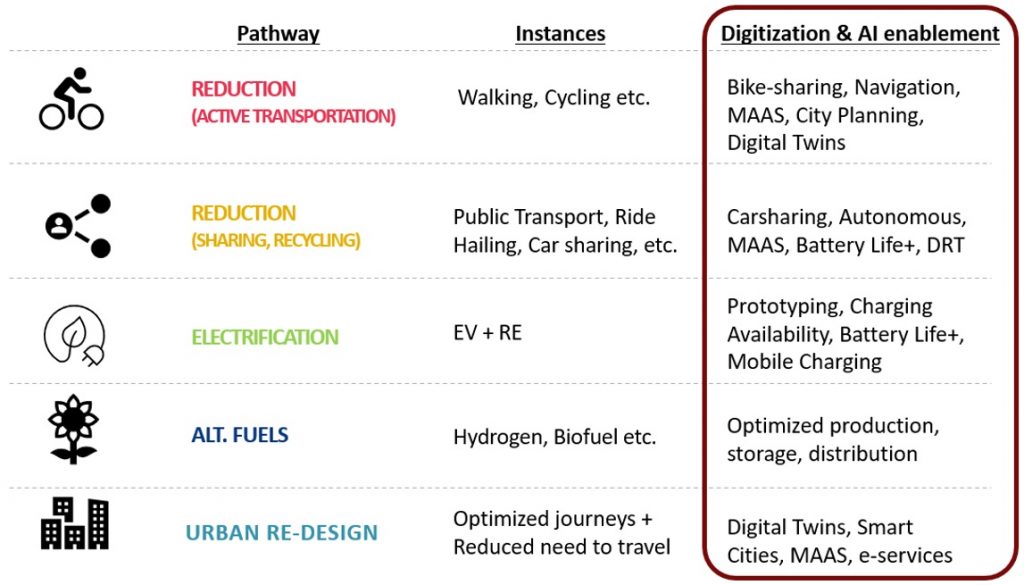

To build truly sustainable transport ecosystems, ASEAN cities must pursue a multi-pronged strategy. There are five key pathways to urban transport decarbonization – each uniquely empowered by AI and digital technologies:

| 1. | Reduction through Active Mobility |

| Walking, cycling, and other active modes form the foundation of green mobility. Digital tools such as bike-sharing platforms, smart navigation, Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), and city planning through digital twins amplify this shift. | |

| 2. | Reduction through Sharing and Circularity |

| Public transport, ride-hailing, and car-sharing become more efficient when optimized via autonomous systems, demand prediction, and integrated digital platforms for shared mobility. | |

| 3. | Electrification |

| EV adoption must be supported by AI-enabled charging infrastructure, battery management, and mobile charging solutions to ensure scalability and convenience. | |

| 4. | Alternative Fuels |

| Hydrogen and biofuel systems benefit from AI’s ability to optimize production, storage, and distribution – making alternative fuels commercially and operationally viable. | |

| 5. | Urban Re-design |

| Reducing the need to travel by rethinking city layouts – with the help of digital twins, smart city tools, and e-services – can dramatically shrink transport emissions. |

Figure 2: AI-enabled pathways to decarbonize urban transport

While the five pathways provide clear directions, real progress demands convergence – a seamless integration of multiple technologies, platforms, and data ecosystems. This is where AI and digital technologies become the unifying force.

Modern sustainable transport solutions rely on a complex interplay between:

| 1. | Future mobility technologies such as multimodal autonomous fleet management, augmented/virtual reality (AR/VR), and metaverse-based modeling |

| 2. | Smart city platforms that include traffic control centers, AI-powered analytics, geospatial and IoT systems, and curbside management |

| 3. | Connected mobility solutions, such as cloud-based data sharing, open APIs, real-time traffic monitoring, and integrated MaaS platforms |

| 4. | Independent mobility infrastructure, including smart charging, predictive maintenance systems, fleet optimization tools, and dispatch algorithms |

The convergence of these systems shifts urban transport from fragmented legacy operations toward a cohesive, intelligent network. It enables cities to predict congestion, optimize routes, personalize commuter experiences, and dynamically respond to shifting demand – all in real time. More importantly, it supports resource-efficient urban design, where AI informs everything from investment planning to energy use to spatial zoning.

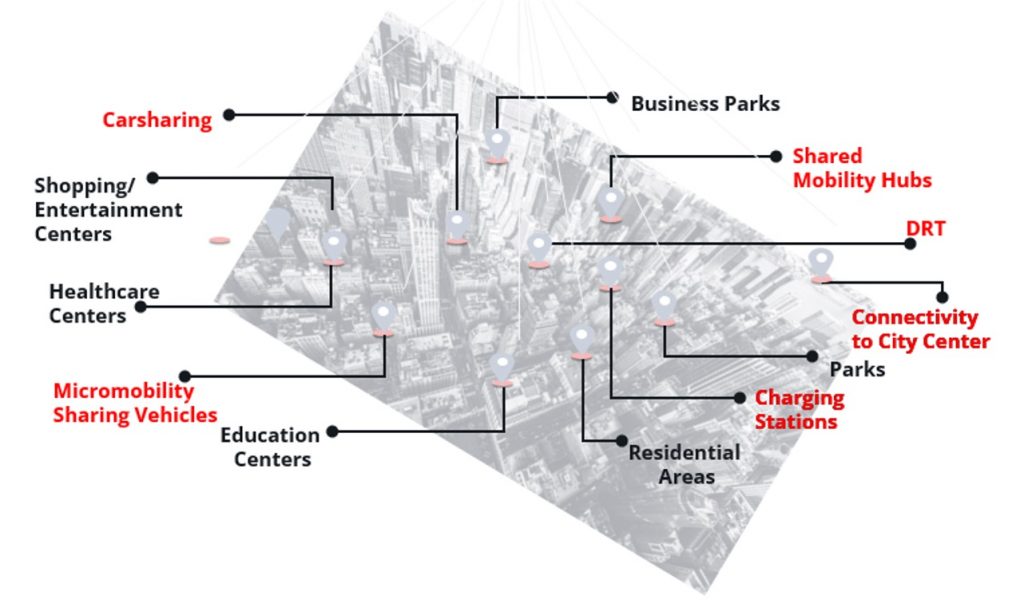

One of the most promising urban planning frameworks for sustainable, inclusive cities is the “15-minute city”[3] – a concept where residents can access work, education, healthcare, retail, and recreation within a 15-minute walk or ride from their homes. Cities like Paris and Melbourne are leading this transition, while Singapore and Dubai are beginning to adapt the model to their own urban realities.

What makes this model viable in dense, fast-growing ASEAN cities is the integration of AI and digital technologies, which serve as essential enablers at every stage of implementation.

| 1. | Smarter city planning |

| Digital tools help urban planners analyze real-time transport trends, commuting patterns, and land-use parameters to optimize where services, amenities, and transport infrastructure should be located. Digital twins – virtual replicas of urban environments – allow simulations that improve decision-making and planning precision | |

| 2. | Connected mobility infrastructure |

| AI and IoT technologies enable demand-responsive transport (DRT) systems, allowing users to efficiently access shared mobility services (like EV buggies or micro transit) efficiently based on live demand. Dynamic pricing algorithms optimize fares according to time, location, and congestion, enhancing system efficiency and revenue potential | |

| 3. | Public-private monetization models |

| With increased digital control over streets and transport access points, cities can generate revenue through curbside monetization – charging logistics providers, delivery vehicles, or ride-hailing services for prioritized access or parking. These mechanisms not only help regulate urban space usage but also unlock new sources of municipal finance to fund sustainable infrastructure | |

| 4. | Equity and access |

| Digital systems can also ensure that mobility is inclusive, addressing the needs of children, the elderly, and disadvantaged communities |

In essence, the 15-minute city is more than just a walkable neighborhood – it’s a digitally intelligent ecosystem, enabled by AI and connected infrastructure, offering cleaner air, reduced travel times, better quality of life, and stronger local economies.

Figure 3: Digital and AI enablement of the 15-minute city

As ASEAN cities transition toward smart mobility, several challenges must be addressed:

| ・ | Technological gaps in localization and cybersecurity |

| ・ | Infrastructure limitations, especially in EV charging and real-time data systems |

| ・ | Policy hurdles, such as outdated licensing frameworks and absent carbon pricing |

| ・ | Cultural resistance to AI and shared mobility |

| ・ | Funding constraints, due to unclear ROI timelines |

| ・ | Fragmented data systems, with poor standardization and reliability |

Addressing these challenges will demand cross-sector collaboration among governments, private players, and advisory firms.

IGPI Singapore has been a trusted partner to mobility players navigating structural transformations, digital disruption, and business model innovation. Our extensive project experience spans:

| ・ | Strategic assessments on the impact of CASE (Connected, Autonomous, Shared, and Electric) on auto manufacturing globally |

| ・ | Go-to-market strategies for battery and EV solutions across Asia |

| ・ | Business model development for digital and financial solutions in mobility |

| ・ | Digital transformation enablement, including driving school modernization and smart fleet management |

| ・ | Investment support, with IGPI-managed funds backing innovative mobility players across India, Japan, and the Nordics |

Our goal is to help clients design sustainable, AI-enabled, and commercially viable mobility strategies tailored to the ASEAN context.

The future of transport in ASEAN isn’t just electric – it’s intelligent. Digital transformation and AI are not mere support functions, they are strategic levers that determine how inclusive, clean, and resilient our cities become.

At IGPI, we believe that rethinking mobility through the lens of digital innovation can unlock economic opportunity, environmental health, and social equity – all at once.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

[1] EU-ASEAN Business Council (2024): Clean Journeys Ahead – Charting ASEAN’s path towards a decarbonized transport sector

[2] Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago. Air Quality Life Index (AQLI)

[3] The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet (by Carlos Moreno, published in 2024)

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

Harsh Munim, Associate of IGPI Singapore

Harsh is a dynamic professional with an MBA from NUS Business School and a BBA in Finance from City University of Hong Kong, where he also had the opportunity to go on an exchange program to Indiana University Bloomington in the United States. With over 4 years of experience, Harsh brings a wealth of expertise to his role at IGPI. Prior to joining IGPI, he worked as a Senior Project Manager at an investment research firm in Hong Kong, where he managed diverse projects in South East Asia and Oceania. During his MBA, Harsh interned with IGPI, contributing to projects related to carbon credits, microgrids, and the consumer goods industry. He also gained valuable experience at IQVIA, where he supported global pharmaceutical companies on LOE strategy, segmentation, targeting, and go-to-market projects.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

For decades, conglomerates were viewed as lumbering dinosaurs—unwieldy, unfocused, and burdened by internal complexity. Investors punished them with the so-called “conglomerate discount”, assuming that no single leadership team could effectively manage disparate businesses under one roof.

But the tides are turning. In an era defined by industry convergence, digital integration, and AI-enabled insight, conglomerates are discovering that scale and diversity can now be competitive assets rather than liabilities. The age of the conglomerate premium has quietly begun. In addition, large conglomerates are adapting more effectively to the shifting geopolitical situation landscape – marked by rising economic nationalism and trade wars – by building more resilient supply chains and leveraging lobbying power to influence regulations and policies.

The long-promised synergies of conglomerates have remained elusive. Many still struggle with internal silos, rigid data policies, and incompatible systems. Even in sectors where cross-industry collaboration is critical—such as smart cities or healthcare—efforts to share data are often hindered by misaligned incentives or governance friction.

The opportunity cost is enormous. Imagine if property developers could partner seamlessly with mobility providers to optimise urban design, or if banking data could be harnessed to flag early signs of cognitive decline. The technological engines now exist, but the data-sharing architecture still lags behind.

Yet there are bright spots. Some Japanese trading houses, historically diversified by design, are now realising data-driven synergies across business lines. In Southeast Asia, they are developing integrated industrial parks and smart cities, blending expertise in energy, mobility, and real estate under a unified strategic vision. These are not joint ventures in name only; they represent genuine cross-unit collaboration, made possible by aligned data systems and purpose-driven integration.

Government-led efforts are also gaining traction. In healthcare, the sharing of anonymised data across hospitals, insurers, and policymakers is beginning to deliver systemic efficiencies. In finance, unexpected insights are emerging—from internet banking patterns that reveal early signs of dementia, to cross-sector signals that drive innovation in elderly care.

The rise of generative AI could fundamentally transform conglomerates. By ingesting data across divisions—from intellectual property to operations to customer insights—AI can detect patterns, spark innovation, and generate thousands of viable business ideas in minutes. What once took months of internal coordination can now be achieved in seconds.

This is more than efficiency. AI offers a new model of creative integration—surfacing connections that human silos overlook, without forcing cultural convergence or endless alignment meetings. In this light, conglomerates don’t need to be restructured – they need to be rewired.

In emerging markets, this new logic is already producing winners. Take VinGroup in Vietnam: spanning retail, real estate, and EV manufacturing, it has evolved into a multi-industry platform capable of generating and leveraging data across the entire value chain. Its mobility services collect user behaviour that informs smart city development—an advantage that few pure-play rivals can replicate.

Across India and Southeast Asia, similar patterns are emerging. As governments court investment while maintaining complex regulatory environments, conglomerates are often best positioned to navigate policy ambiguity, scale new ventures, and capture market share—faster than their startup counterparts.

The highest-performing conglomerates are not merely bigger—they are strategically coherent. What sets them apart is leadership: CEOs who can define a group-wide purpose that transcends sectors, allocate capital accordingly, and foster collaboration without forcing conformity.

As industry boundaries blur, silo-specific strategies matters less than a shared sense of direction. Asset allocation becomes an act of orchestration, not just budgeting. Purpose replaces rigid planning as the compass for decision-making.

Traditional corporate strategy focused on creative destruction – divest, acquire, pivot. Today’s leaders are turning to creative integration—combining existing assets and capabilities in new ways to generate fresh value. Diversification comes first, integration follows. It’s a more fluid, experimental approach, but no less disciplined.

This represents a shift from the old portfolio mindset. Instead of simply choosing which businesses to back or exit, leaders are rethinking how the pieces fit together. The future belongs to firms that can continually recombine their components—not just add or subtract them.

Corporate venture capital (CVC) was intended to address the innovation challenge. In the West, it often works – modular organisations can more easily absorb and scale startups. In Asia, however, results have been mixed. Highly integrated corporate structures make it harder for external ventures to plug into existing systems.

Startups selected by CVC units may appear promising, but they often stall post-investment—struggling to access networks, customers, or internal capabilities. In such environments, internal new business creation, supported by cross-unit collaboration, may offer a more viable path forward.

The modern conglomerate is not a relic. With AI as connective tissue, data as a shared resource, and leadership grounded in purpose rather than control, the conglomerate is being reborn as an orchestrator of ecosystems.

The discount is fading. The premium is rising. And the playbook is being rewritten.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Not long ago, globalisation seemed unstoppable. Goods, capital, people, and ideas flowed ever more freely across borders. Corporations scaled vertically and horizontally, orchestrating global supply chains from boardrooms thousands of miles away from the markets they served. That was then.

Now, regionalisation is taking centre stage. This is not a retreat from globalisation, but its transformation—a reorientation of economic activity into clusters that are geographically tighter or culturally aligned, though not always physically proximate. The world isn’t merely fragmenting; it is reorganising.

The transition began with internationalisation—the export of high-quality manufactured goods from industrialised nations to the rest of the world. It then evolved into globalisation, as information, labour, and finance began to circulate with greater ease. But in recent years, two forces have accelerated a new shift; the digital revolution and the maturation of emerging economies.

The smartphone has become more than a communications tool—it has a means of production and distribution. What once required entire departments and vast budgets can now be executed by a single individual with access to software and connectivity. The manufacturing sector, too, has evolved. In the case of electric vehicles, modular components and simplified architecture have enabled even start-ups to challenge incumbent automakers. In China alone, hundreds of new EV firms have emerged.

At the same time, rising income levels in countries like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam have shifted the nature of demand. Consumers are more discerning. Local tastes and constraints matter more. Multinationals can no longer impose global templates with impunity. The region has become the unit of competition.

This shift is shaping how organisations make decisions. Where strategy was once determined at corporate headquarters and cascaded down through operational layers, today it is increasingly shaped at the frontline. A motorbike driver in Jakarta using a super-app or a clinic in Manila adopting digital payment trends is no longer just executing a strategy—they are shaping it. Technology enables them to respond to real-time needs in ways centralised command structure never could.

Platforms like Gojek exemplify this evolution. Their services vary meaningfully from city to city, driven by local market dynamics rather than corporate mandates. The role of the executive has changed—from being the architect of strategy to the designer of systems: setting purpose, establishing protocols, and ensuring internal alignment, while allowing decentralised innovation to thrive.

This does not signal the end of scale, but a redefinition of it. Regional platforms are growing not by cloning global models, but by adapting their core philosophies—digital inclusion, local empowerment, logistical infrastructure—to each context. Taobao Villages, for example, born in rural China, are extending their reach to places like Mexico and East Africa. The blueprint remains, but the structure bends to local conditions.

This form of regionalisation resists easy dominance. It demands humility, patience, and a deep understanding of context. Companies cannot rely on brute force or uniform branding. They must localise interfaces, services, and even corporate culture, while maintaining scalable back-ends systems such as pricing algorithms or logistics hubs.

The result is not a balkanised world, but a layered one—where integration takes different forms, and success depends less on size than on relevance. The firms that will thrive are not those with the most resources, but those most attuned to the needs within a five-kilometre radius.

In this new world, regionalisation is not the antithesis of globalisation. It is its evolution—more adaptive, more decentralised, and, perhaps, more resilient.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, Partner of IGPI Group & CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

There was a time when purpose was prepackaged. Life followed a script: study hard, land a job, buy a house, and retire in comfort. Meaning was socially constructed and widely shared. To succeed, one simply followed the rules.

That era has passed. Today, individuals are freer-perhaps even too free. With tradition in retreat and institutions in flux, the burden of defining meaning has shifted from systems to selves. We are no longer choosing between clear paths; instead, we are now tasked with inventing them. Strategy, which was once a question of how, has become a question of why.

As collective beliefs dissolve, a peculiar phenomenon emerges: the elevation of tactics into ideology. When the destination is uncertain, people cling to the map. Education becomes sacred. Wealth becomes virtue. Process becomes principle. In this void, the means are often mistaken for the ends.

In corporate life, this appears as process worship: the KPI becomes king, and the playbook becomes scripture. In parenting, it emerges as academic fundamentalism. In governance, it breeds procedural paralysis.

These are not strategies; they are symptoms of strategic disorientation.

In simpler times, such patterns worked. When “success” meant job security, or when “happiness” was synonymous with home ownership, fixed methods were efficient. Today, however, those outcomes have become abstract. We now speak of self-actualization, personal meaning, and authenticity. These are concepts too fluid for rigid tools. Yet many still chase metrics that no longer measure anything real.

This shift marks a profound transformation in the nature of strategic work. In the industrial age, strategy meant optimization: doing known things better. In the post-industrial age, it means orientation. The focus is now on deciding which things matter at all.

Japan is a case in point. Despite its safety, infrastructure, and relative prosperity, it consistently ranks low on global happiness indices. The explanation cannot be material; it is existential. The answer lies in the gap between the measurable and the meaningful.

Even branding reflects this shift. Once built on functional and emotional value, modern brands now trade in identity. Products are no longer merely useful or delightful; they are aspirational. They promise not just performance, but transformation. In this new “purpose economy,” the product is not the object itself. Instead, it is the self the object allows us to become.

The implications for leadership are profound. Strategy must now account not just for markets or operations, but also for mindsets. Leaders are no longer navigators of terrain. They are designers of direction, responsible for holding space for ambiguity, stewarding identity, and anchoring people in a world where everything-including purpose-must be self-defined.

This shift brings risk. In systems built for predictability, ambiguity can be destabilizing. In cultures of bottom-up consensus, belief in method becomes deeply ingrained. In top-down systems, rapid pivots are possible, but often come at the cost of depth and coherence. Each approach has strengths, but both risk misalignment in a world where context evolves faster than culture.

What is needed is not new ideology, but strategic adaptability. Organizations must develop the ability to reconfigure structures, not just goals. We need systems that can learn and evolve.

The old question, “What should we do?” must now be preceded by a harder one: “What are we aiming for?” That question cannot be answered by data alone. It requires judgment, perspective, and, above all, thoughtful design.

In this new landscape, the manager is no longer simply a planner. She is a philosopher with a P&L. The strategist is no longer just a tactician. He is a curator of collective meaning. It is no longer about finding the fastest route. It is about deciding what is truly worth the journey.

Strategy, in short, has become stewardship.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

In a recent conversation between Kohki Sakata (CEO, IGPI Singapore) and Shivaji Das (MD, IGPI Singapore), the two explored what’s making Japan attractive today, what sectors present the greatest opportunities, and how foreign firms can succeed in one of Asia’s most complex markets.

Several recent factors are converging to attract renewed global interest in Japan. The weakening yen and the relatively low valuation of listed Japanese companies have made the market especially appealing, especially from an M&A perspective. Many firms on the Tokyo Stock Exchange are trading below book value, opening the door to both activist and strategic investment.

Beneath these financial signals lies a deeper structural story. Japan is facing issues that many other countries will soon encounter—an aging society, declining population, and aging infrastructure. These legacy systems, often highly dependent on human labor, represent urgent social challenges—and untapped market potential for companies offering scalable, tech-enabled solutions.

Infrastructure is emerging as one of the most promising sectors. Japan’s centralized models for water supply, energy, and transportation—built in the 20th century—are becoming increasingly outdated. In their place, decentralized systems such as microgrids or modular water technologies, already common in emerging markets, are becoming viable and cost-effective options even in Japan’s suburbs and regional cities.

In B2C, particularly in healthcare, significant gaps also present clear opportunities. While many countries have adopted telemedicine as a core part of their healthcare infrastructure, Japan continues to rely on in-person consultations. The infrastructure, technology, and user behavior in Japan are ripe for transformation—especially following the global acceleration of digital healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic.