India holds significant potential in high-tech manufacturing, underpinned by its vast domestic market and a deep reservoir of engineering talent. However, several structural challenges continue to impede its ability to compete with established players such as China, South Korea, Japan, and the United States.

One of the most pressing obstacles is access to advanced technology. Unlike its global competitors, India lacks well-developed technology clusters in critical sectors such as semiconductors, aerospace, and medical devices. This reliance on foreign collaborations and technology transfers not only limits autonomy but also creates vulnerabilities in strategically sensitive industries.

Another challenge lies in the absence of a robust high-tech manufacturing ecosystem. India’s industrial base lacks the depth of supply chain linkages and partnerships necessary for rapid scaling. Global firms are often hesitant to collaborate with Indian manufacturers due to limited experience in cutting-edge production. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where the lack of credentials prevents Indian firms from integrating into high-value global supply chains.

Furthermore, India faces a significant talent retention issue. Despite producing a large number of engineers and technical professionals annually, many migrate to higher-paying markets abroad. This brain drain exacerbates workforce shortages in critical areas of high-tech manufacturing.

Despite these challenges, India’s achievements in low-tech manufacturing provide a strong foundation for its high-tech aspirations. By building on this base, India can create spillover benefits that accelerate its transition to advanced manufacturing.

Infrastructure development offers a clear pathway for this transition. Addressing long-standing issues such as energy reliability and logistical inefficiencies will not only benefit low-tech industries but also enhance the viability of high-tech sectors. For instance, improving transport networks and energy supply chains can reduce bottlenecks that hinder high-end manufacturing.

Workforce development serves as another critical bridge between low- and high-tech industries. Structured vocational training programs tailored for low-tech sectors can gradually upskill workers for more sophisticated applications. This approach ensures a steady pipeline of talent capable of supporting India’s high-tech ambitions.

Traditional manufacturing ecosystems have historically been organized around vertically integrated value chains, with tightly linked networks of suppliers, OEMs, and manufacturers. However, the digital revolution has disrupted this paradigm, giving rise to more modular and dynamic production systems.

The smartphone industry exemplifies this shift. Telecommunications providers, software developers, operating system creators, and device manufacturers now operate within distinct yet interconnected layers rather than rigid value chains. This layered structure fosters greater flexibility and efficiency by allowing firms to specialize in specific segments of the value chain.

For India to compete effectively in high-tech manufacturing, it must embrace this new paradigm. Rather than replicating traditional supply chains dominated by established players, Indian firms should focus on identifying lucrative niches within these layered structures. Specialization will enable Indian manufacturers to carve out competitive advantages in global markets.

India’s potential as a high-tech manufacturing leader is most pronounced in sectors where demand is growing rapidly and foundational strengths already exist:

| ● | Medical Devices: While India has established itself as a producer of basic medical equipment like blood pressure monitors, it has yet to make significant strides in advanced devices such as MRI machines. Strengthening production capabilities could position medical devices as a cornerstone of India’s high-tech ambitions. | |

| ● | Aerospace and Defense: Recent efforts have focused on component production and airframe assembly. Expertise in advanced materials engineering and precision manufacturing will be critical for scaling this sector. | |

| ● | Space Technology: Building on ISRO’s success in cost-efficient satellite launches, India has an opportunity to expand into commercial satellite manufacturing. | |

| ● | Semiconductors: With geopolitical shifts prompting supply chain diversification away from China, India is well-positioned to attract investments in semiconductor design and fabrication. |

Though in a different context, China’s rapid ascent in high-tech manufacturing offers potential lessons for India’s path forward:

| 1. | Talent Development: China prioritized STEM education to ensure a steady pipeline of engineers and technicians. | |

| 2. | Government Incentives: Targeted subsidies and R&D grants enabled Chinese firms to scale rapidly. | |

| 3. | Technology Transfers: By mandating joint ventures with foreign firms, China secured access to advanced technologies that bolstered domestic capabilities. |

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) will play an indispensable role in advancing the nation’s high-tech manufacturing capabilities. Beyond capital infusion, FDI brings global best practices and cutting-edge technologies that enhance competitiveness. To mitigate risks associated with geopolitical fragmentation, India must diversify its FDI sources by engaging with multiple countries.

To attract global investors and technology partners, Indian policymakers must address regulatory complexities that deter foreign firms. Simplifying tax structures and easing compliance requirements will create a more conducive environment for investment.

Equally important is fostering competition rather than overprotectionism. Industries shielded by excessive government intervention often struggle to remain globally competitive. Encouraging open competition will drive innovation and efficiency across sectors.

India possesses the market size, talent pool, and industrial foundation needed to emerge as a global leader in high-tech manufacturing. Success will hinge on its ability to overcome structural challenges while leveraging opportunities through strategic investments and policy reforms. By embracing modular industry structures and drawing lessons from global best practices, India can position itself at the forefront of the high-tech revolution. The next decade will be pivotal—will India rise to meet the challenge?

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

India’s early industrialization efforts in the 1950s and 1960s were state-driven, with a heavy reliance on public sector enterprises in industries such as steel, aerospace, and defense manufacturing. However, this approach led to systemic inefficiencies, an absence of competitive pressure, and limited access to cutting-edge technology.

Additionally, India’s economy remained highly protectionist, restricting foreign investments and market competition. With limited exposure to global best practices and a constrained talent pool in high-tech fields, the country struggled to establish a meaningful presence in advanced manufacturing. The result was a missed opportunity in high-tech sectors, with India unable to capitalize on its early ambitions.

In stark contrast to its high-tech struggles, India’s pharmaceutical industry thrived despite lacking full vertical integration. The turning point came as global drug patents expired, opening opportunities for low-cost generic manufacturing. Initially reliant on European and Japanese suppliers for raw materials, Indian firms later leveraged Chinese manufacturers for cost-effective inputs, allowing them to scale rapidly.

This layered approach—focusing on specific segments of the value chain rather than attempting full vertical integration—enabled India to dominate the global generic pharmaceutical market. By specializing in cost-efficient manufacturing and regulatory expertise, Indian firms carved out a niche in a heavily commoditized industry, demonstrating that strategic positioning within a value chain can sometimes outweigh full control over it.

For decades, China dominated the global toy industry, particularly in South China, controlling over 80% of global market share. However, India has recently emerged as a challenger, driven by a combination of government protectionist policies, a booming domestic market, and localized product innovation.

Historically, India had a strong domestic toy industry focused on traditional, handcrafted toys, but lacked large-scale manufacturing capabilities. Recent government incentives, coupled with rising middle-class purchasing power, have enabled Indian manufacturers to scale up production and cater to both domestic and international markets. Unlike China, which dominates through mass production, India is differentiating itself by leveraging its cultural heritage—customizing toys to reflect regional preferences and traditional aesthetics.

This success reflects India’s broader industrial strategy: leveraging domestic strengths to create export opportunities, rather than directly competing with China’s economies of scale.

India’s industrial conglomerates have played a defining role in shaping the country’s manufacturing landscape, but their origins differ significantly from their Chinese counterparts.

While Chinese conglomerates often trace their roots to banking, finance, or real estate, Indian business houses emerged from trading and commerce. Historically, trading families from Gujarat, Rajasthan, and the Parsi (Iranian) diaspora built extensive networks with the Gulf, Africa, and Europe, later expanding into manufacturing and industrial sectors.

When India’s economy was heavily regulated, these conglomerates diversified across multiple industries to navigate restrictions and survive. However, post-liberalization, many of them restructured and consolidated, focusing on sectors where they could achieve global competitiveness.

This evolution has created a fundamental difference in industrial structures:

| ● | China’s manufacturing model is vertically integrated, with companies controlling multiple stages of production. | |

| ● | India’s model remains horizontally integrated, with firms specializing in specific segments of the value chain rather than fully owning upstream and downstream processes. |

This structural distinction has implications for India’s future in high-tech manufacturing—can it replicate China’s model, or should it refine its own unique approach?

The Indian government has been both an obstacle and a catalyst for manufacturing growth. In the past, high import tariffs and nationalization efforts sheltered domestic industries but limited their competitiveness. Today, however, India has embraced a more market-driven approach, introducing:

| ● | Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) to encourage domestic manufacturing. | |

| ● | Infrastructure investments in roads, power, and logistics. | |

| ● | Tax reforms such as GST (Goods and Services Tax) to harmonize the regulatory landscape. |

These policies have lowered costs, improved supply chain efficiency, and incentivized foreign investments, making India a more attractive manufacturing hub.

India’s biggest advantage is its massive domestic market, which few low-tech manufacturing hubs can match. Unlike countries such as Bangladesh (focused on textiles) or Vietnam (electronics), India benefits from sectoral diversity, spanning pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals, medical devices, and even aerospace.

This breadth of expertise allows India to compete across multiple verticals, rather than being dependent on a single industry. Additionally, India’s labor force, while still in transition, offers a balance between cost competitiveness and technical capability.

India’s manufacturing landscape today is split into two parallel worlds:

| 1. | Globally integrated, world-class manufacturers—leveraging IoT, AI-driven inventory management, and predictive analytics to optimize efficiency. | |

| 2. | Fragmented, low-tech enterprises—often informal, small-scale, and slow to adopt digital tools. |

While large corporations have embraced Industry 4.0 innovations, smaller enterprises remain largely untouched by digitalization. Bridging this gap is crucial for India’s broader industrial transformation. To stay competitive, India must accelerate digital adoption at all levels—integrating small-scale manufacturers into modern supply chains and enabling them to compete globally.

The low-tech industrial foundation has provided it with a strong cost-competitive base, but its future lies in scaling high-tech industries. The transition from horizontal diversification to vertical specialization will require:

| ● | Greater investment in R&D to drive innovation. | |

| ● | Stronger policy support for high-tech sectors. | |

| ● | Global partnerships to accelerate technology transfer. |

As India positions itself for the future, the central question remains: Can India replicate China’s vertically integrated manufacturing success, or will it forge its own distinct, layered approach? The answer to this will define India’s global industrial role in the decades ahead.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

China’s vertically integrated model provides greater control over supply chains, cost efficiency, and innovation synergies. This model has helped China dominate industries such as electronics, automotive, and industrial manufacturing, where deep coordination between suppliers and producers is crucial. A prime example is China’s semiconductor industry, where state investment has strengthened domestic chipmakers, reducing reliance on foreign technology. However, this model also faces challenges, particularly in overcoming technological dependencies and geopolitical constraints.

India, by contrast, follows a horizontal specialization model, where different firms focus on specific segments of the value chain. This approach requires less capital investment, encourages global partnerships, and aligns well with industries where R&D and production can be geographically dispersed. In the automotive sector, for instance, Indian firms such as Tata Technologies and Infosys provide digital engineering and automation solutions for global car manufacturers, bridging software and manufacturing without full-scale production facilities.

India’s pharmaceutical industry exemplifies the benefits of horizontal integration, particularly in the generic medicine sector. India is the world’s leading supplier of generic drugs, accounting for over 40% of the U.S. market. Unlike China’s vertically integrated pharmaceutical sector, India has succeeded by leveraging a combination of process patents, cost-efficient production, and strategic global partnerships.

Sun Pharmaceutical Industries is a case in point. Initially focused on generics, the company later expanded into specialty and branded drugs through acquisitions, demonstrating how horizontal integration enables value-chain upgrades. Similarly, firms like Biocon and Dr. Reddy’s have leveraged their strengths in generics to enter the contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) space, working with multinational pharmaceutical companies on advanced drug development.

While India initially built its pharmaceutical success on cost efficiency, it is now moving up the value chain into biologics, specialty medicines, and high-end research. This shift illustrates how horizontal models can evolve to capture higher-value segments, reinforcing India’s growing influence in the global pharmaceutical landscape.

Despite its dominance in pharmaceuticals, India lags behind in medical device manufacturing, a sector historically controlled by global giants such as GE, Siemens, and Toshiba. However, the industry is undergoing a transformation, shifting from hardware-driven products to service-based, software-integrated solutions.

For India to establish itself as a global player in medical devices, it must strengthen its local supply chains, encourage deeper collaboration between universities and industry, and leverage government incentives to attract investment in domestic production. The transition to a more digital and services-driven healthcare model presents a strategic opportunity for India to integrate its software strengths with traditional manufacturing capabilities.

Beyond pharmaceuticals and medical devices, India’s software industry is reshaping global manufacturing by shifting value from physical production to data-driven services. In the automotive sector, the growing emphasis on connected vehicles and autonomous systems has made India a key hub for automotive software development. Meanwhile, smart grid solutions and predictive analytics are modernizing energy networks, while AI-driven predictive maintenance is improving factory efficiency worldwide.

Bosch India’s operations exemplify the evolving nature of global manufacturing. The company has strategically leveraged India’s AI expertise to optimize its production networks worldwide. This integration of advanced software capabilities into manufacturing processes underscores the increasing centrality of digital technologies in modern industrial operations, potentially offering Bosch a competitive edge in efficiency and innovation.

While India has significant strengths in software and digital transformation, its manufacturing sector faces structural challenges. One key issue is workforce readiness. India’s workforce is comparable in size to China’s, but literacy rates, advanced manufacturing skills, and female labor force participation remain significantly lower. In manufacturing-driven economies, these factors influence productivity and industrial scalability.

China has benefited from a strong, state-driven industrial policy that has supported manufacturing through large-scale infrastructure investment, subsidies for priority sectors, and strict technology transfer requirements for foreign firms. In contrast, India has taken a more market-driven approach, though recent policy reforms are addressing historical bottlenecks. Initiatives such as the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme are helping boost local manufacturing, while deregulation of labor laws and improvements in ease of doing business have made India a more attractive destination for industrial investment.

India’s emerging toy manufacturing industry presents an interesting case of policy-driven industrial growth. Recent government initiatives, including local content requirements and tariff adjustments, have reshaped the competitive dynamics of this sector. As a result, India has begun to capture a growing share of the global toy production market, a space traditionally dominated by Chinese manufacturers. This shift highlights the potential impact of aligned government policies and industry needs in developing new manufacturing capabilities.

Traditional value chain analysis is no longer sufficient for understanding global industries. As manufacturing becomes more software-driven, companies must move beyond sector-based strategies and adopt a layered approach, considering the integration of software with traditional industries, the rise of data-driven, subscription-based business models, and the increasing interdependence of manufacturing, AI, and IoT.

This shift requires firms to rethink supply chains, innovation models, and global partnerships. Companies that can successfully navigate this transformation by integrating software with traditional production and leveraging cross-industry collaboration will be best positioned to lead in the next phase of global industrial evolution.

India and China represent two distinct pathways to manufacturing success. China’s vertically integrated model has allowed it to achieve dominance in scale-driven and infrastructure-heavy industries, while India’s specialization model has enabled it to succeed in technology-driven and service-enhanced sectors.

As technology reshapes industry boundaries, firms must rethink their manufacturing strategies. The future of global manufacturing will not be defined by a single model but by the ability to integrate digital capabilities, optimize global partnerships, and embrace the layered industrial transformation that is already underway. Companies that successfully adapt to this changing landscape will emerge as leaders in the next era of global industry.

IGPI possesses extensive experience supporting companies in aligning their manufacturing strategies with either vertical or horizontal integration models, depending on their industry and market needs. By considering strategic trade-offs, we can help businesses optimize their processes to retain competitiveness.

To find out more about how IGPI Group can provide support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Kohki Sakata, CEO of IGPI Singapore

After joining Cap Gemini and Coca Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. After joining IGPI, he has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions that has been developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turnaround Asian companies with focus on setting clear vision and employee empowerment. Kohki has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management.

He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Shivaji Das, Managing Director of IGPI Singapore

Shivaji has over 20 years of strategy consulting experience, specializing in New Business Models, Innovation Roadmaps, and Sustainability Journeys. He has worked with private and public sector clients across 25 countries in sectors like Technology, Semiconductors, Chemicals, Healthcare, Renewable Energy, and Construction. Previously, Shivaji was a Partner and Managing Director-APAC at Frost & Sullivan. His paper on Artificial Intelligence was presented at CAINE-2000 in Hawaii, USA. He is the author of seven acclaimed travel, art and business books including The Visible Invisibles and Rebels, Traitors, Peacemakers (both Penguin Random House), as well as The Great Lockdown: lessons learned during the pandemic from organizations around the world (Wiley, USA).

He is an alumnus of IIT Delhi and IIM Calcutta.

IGPI Group is a Japan rooted premium management consulting & Investment Group headquartered in Tokyo with a footprint in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne, as well as parts of Europe and India. The organization was established in 2007 by former members of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turn-around projects in Japan. IGPI Group has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation to name a few. IGPI Group has vast experience in supporting Fortune 500s, Govt. agencies, Universities, SMEs and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has ~8,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

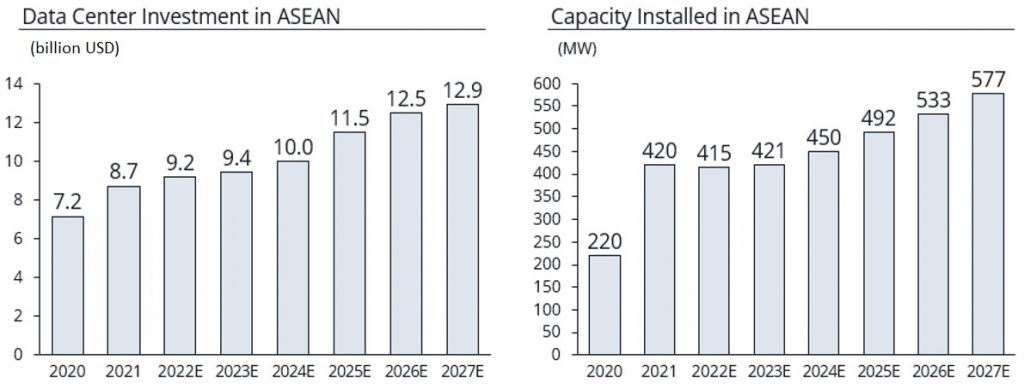

The Southeast Asia data center market is one of the fastest-growing globally, driven by several key factors. The adoption of cloud-based services is expected to be a major growth driver in the coming years. Additionally, Singapore is set to become the first country in the region to implement 5G technology, with Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam also planning and investing in 5G network deployment in the next 5 years. This will further increase data generation, necessitating data centers to manage more complex network traffic. Moreover, the growing demand for generative AI, which requires substantial computational power and vast amounts of data storage, is expected to further drive the need for data center resources.

Graph1. Data Center Market Forecast in ASEAN[1]

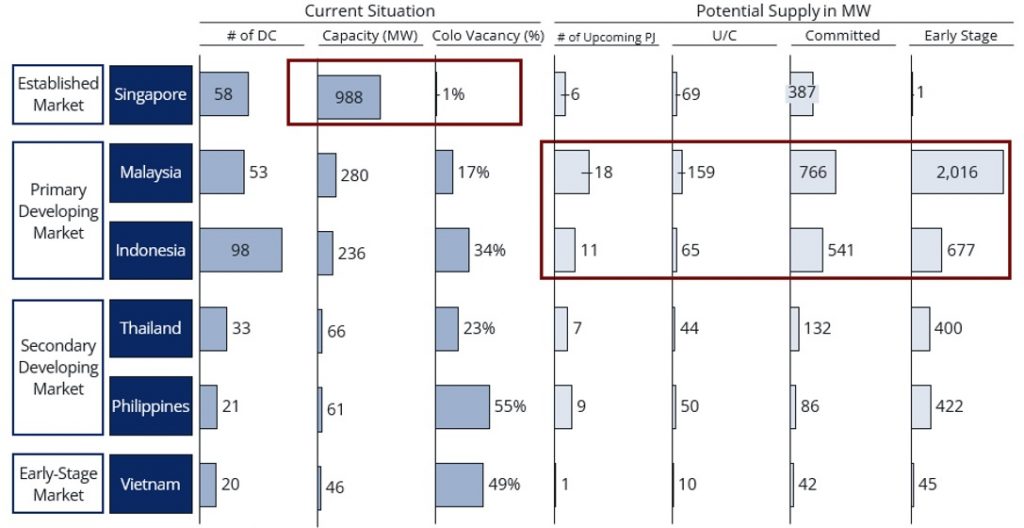

The maturity of the data center market in ASEAN countries is as follows:

Table1. Number of Data Centers with Capacity and The Breakdown of Upcoming Projects by Stage[2]

Singapore is the most mature market in the region. In the APAC area, it ranks second only to Tokyo, with 1GW of operational capacity and a remarkably low vacancy rate of just 1%. In 2019, concerned about the increase in power consumption and the environmental impact caused by the rapid surge in data centers, the Singapore government imposed a moratorium on new data center construction. However, this moratorium was lifted in 2022, and in May 2024, the government announced the “Green Data Center (DC) Roadmap,” which includes goals such as providing at least an additional 300 megawatts (MW) of capacity in the near future and expanding capacity further through the adoption of green energy.

Indonesia and Malaysia are fast-growing markets with enormous supply potential, further driving data center growth in ASEAN. In Malaysia, data center investments are rapidly increasing, particularly in Kuala Lumpur and Johor, while in Indonesia, Jakarta is seeing a surge in investments. This growth is driven by the expansion of the digital economy, the rise of cloud adoption, and hyperscalers such as GAFAM and major Chinese tech players investing in the region. In Malaysia, the government is also working on implementing a regulatory framework focused on sustainability.

Most of the new data centers to be built in the near future will be hyperscale facilities. For instance, out of 18 upcoming projects in Malaysia, 11 are designed as hyperscale, similar to 6 out of 11 in Indonesia and all 9 upcoming projects in the Philippines. This trend towards larger, higher-performance data centers is fueled by advancements in AI technologies.

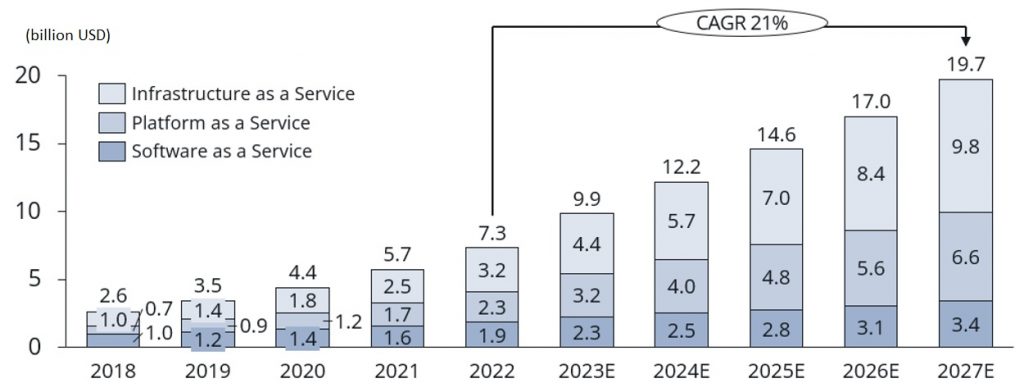

The increasing use of cloud computing in both the public and private sectors in Southeast Asia is a key factor driving the demand for data centers.

For example, the Singapore government set a target to migrate most of its less sensitive digital workloads to the commercial cloud by 2023 and successfully achieved it. Similarly, many large companies in Singapore’s private sector have begun adopting cloud services, utilizing these solutions to implement advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning.

In 2021, the Malaysian government introduced a cloud-first strategy in the public sector to increase cloud adoption rates to 50% by 2024.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s cloud computing market has experienced remarkable growth, with a CAGR of 48%, over the last 5 years, according to CNBC Cloud. This surpasses the global average, and currently, 90% of companies in Indonesia are moving towards cloud computing solutions.

Amid these trends, the cloud market in ASEAN is expected to grow at a 21% CAGR.

Graph2. Public Cloud Market Revenue in ASEAN by Segment[3]

Additionally, to meet the growing demand for data storage and processing, major cloud providers are expanding into the ASEAN region. For example, in 2024, Microsoft announced several significant investments. In April, the company committed $1.7 billion to build new cloud and AI infrastructure in Indonesia over the next four years. In May, Microsoft pledged $2.2 billion to further develop digital infrastructure in Malaysia and also announced its first regional data center, focused on providing AI training opportunities, although the investment amount was not disclosed.

Table2. Area Coverage of Major Cloud Provider in ASEAN[4]

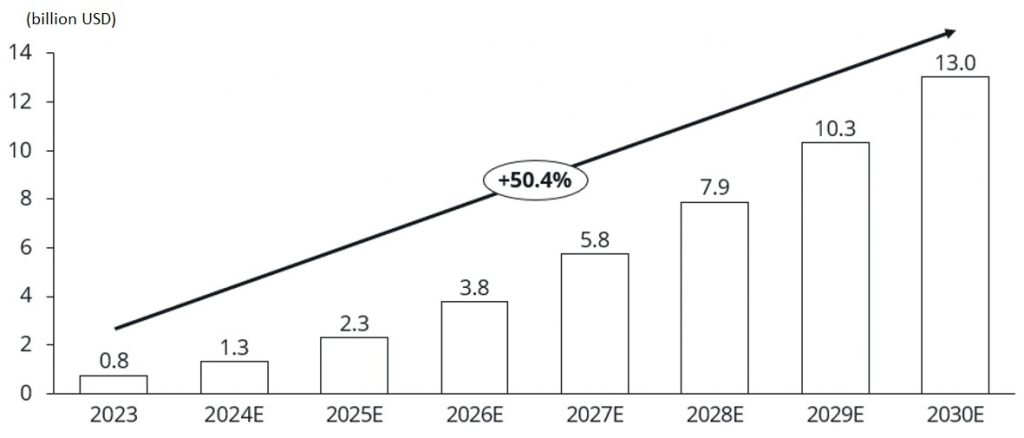

The generative AI market is growing rapidly in Southeast Asia. Currently valued at $0.8 billion, it is expected to reach $13 billion with a 50% CAGR by 2030.

Graph3. Generative AI Revenue Forecast (ASEAN) as of Mar 2024[5]

Indonesia, ranked sixth globally for its number of startups, is experiencing significant growth in generative AI applications, such as chatbots. One example is Kata.ai, which focuses on natural language processing to provide AI-powered conversational chatbots, helping businesses engage with customers more effectively. Kata.ai has a proven track record with major telecommunications companies and state-owned banks. Mekari, a leading SaaS company, also entered the generative AI business in 2023, offering tailored advice on management strategies by analyzing clients’ financial and HR data.

Advances in generative AI are driving increased demand for new types of data centers. Generative AI models, particularly large-scale language models (LLMs) and image generation models, require immense computational resources for both training and inference. This necessitates specialized hardware, including large numbers of GPUs and TPUs (Tensor Processing Units), which are more expensive than conventional CPU-based systems. These specialized systems also require more power and cooling, and take up more physical space, fueling demand for higher-performance and larger data centers, such as hyperscale data centers. Over the next 6 years, the average data center capacity is expected to double, while total capacity is projected to triple.

As generative AI technologies become more widespread, the computational load will increase, leading to higher power consumption. To illustrate, generating a response from ChatGPT requires roughly ten times the energy of a traditional Google search. Based on 9 billion searches per day, this translates to an additional 10 terawatt-hours of energy consumed annually (according to a report by the International Energy Agency, IEA). Furthermore, as computational loads increase, so does the heat generated by servers, which in turn drives up the energy needed for cooling. It’s estimated that cooling accounts for about 30-40% of a data center’s total energy consumption. Overall, the IEA has announced that the power consumption of data centers could double by 2026 compared to 2024 levels.

As power consumption in data centers increases due to the use of generative AI and other technologies, several challenges arise. These include whether we can meet the new energy demands, what types of energy will be used to supply this demand, and how these needs can be balanced with decarbonization goals. However, these challenges present new business opportunities for those who can provide solutions.

[Increasing Energy Efficiency in Data Centers]

One approach is offering hardware and software services aimed at reducing power consumption and improving the efficiency of data centers. For example, the Singaporean startup KoolLogix provides thermal management solutions for data centers. KoolLogix reduces the power consumption of data centers by implementing an innovative cooling system that addresses the inefficiencies of traditional cooling methods. Their system focuses on removing the waste heat generated by servers using a passive heat exchange and phase change approach. Instead of relying on energy-intensive air conditioners, the KoolLogix system uses the servers’ waste heat to power a refrigerant-based cooling loop. This system operates without mechanical pumps or compressors, relying on natural convection, which significantly lowers energy consumption.

[Providing Green Energy to Data Centers]

Another approach is building infrastructure to supply clean energy to data centers. This could include constructing power plants that utilize renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, or geothermal power. These plants would then supply clean electricity to data centers through long-term contracts. In this model, power generation companies sign Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) with data center operators to provide predictable, long-term energy at stable prices.

One example is an initiative launched in Japan in April 2024. Green Power Investment Corporation (GPI) and Kyocera Communication Systems Co., Ltd. (KCCS) are collaborating on a local renewable energy production and consumption model aimed at supplying a zero-emission data center with clean energy. Specifically, GPI’s subsidiary, Green Power Retailing LLC (GPR), will procure electricity generated by the Ishikari Bay New Port Offshore Wind Farm through a specified wholesale supply of renewable energy. This power, along with FIT non-fossil certificates with tracking from the Ishikari Bay wind farm, will be supplied to KCCS’s Zero Emission Data Center (ZED), which is scheduled to open in autumn 2024 in Ishikari City, Hokkaido, and will be operated entirely on renewable energy.

Since its establishment in 2013, IGPI Singapore has supported many Japanese companies with market research, strategy planning, and execution support, including partner search and approach, ideation, and related training for new business creation in Southeast Asia.

Leveraging the extensive insights gained through involvement in the management of data center-related companies in Japan, along with its strong network of data center players in the ASEAN region, IGPI Singapore is well-positioned to offer consulting services. These services include market entry strategies and the development of partnerships with local players in the data center industry. Through on-the-ground research conducted by local staff in ASEAN, IGPI Singapore stays informed about real-time trends in the region’s data center market. This knowledge allows IGPI Singapore to craft effective market strategies and identify potential partners.

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

[1] Arizton

[2] Data Center Map, DC Byte (Apr 2024), Cushman & Wakefield (Apr 2024)

[3] Statista

[4] IGPI Research. As per public disclosure, Mar 2024

[5] Statista

Mr. Jongwoo Lee is the Manager of IGPI Singapore. He worked for a Japanese general IT consulting firm, where he was involved in numerous projects such as business planning and implementation support, new business planning, operational efficiency improvement, and business management enhancement support in a wide range of industries, including trading companies, energy, manufacturers, automobiles, and systems, etc. After joining IGPI, he has extensive experience in new business creation in Southeast Asia, including the development of new business models and strategies for expanding sales of new solutions in the Southeast Asian market and the study of new business entries for local companies in Southeast Asia. Graduated from the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Economics. Japanese Certified Public Accountant

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

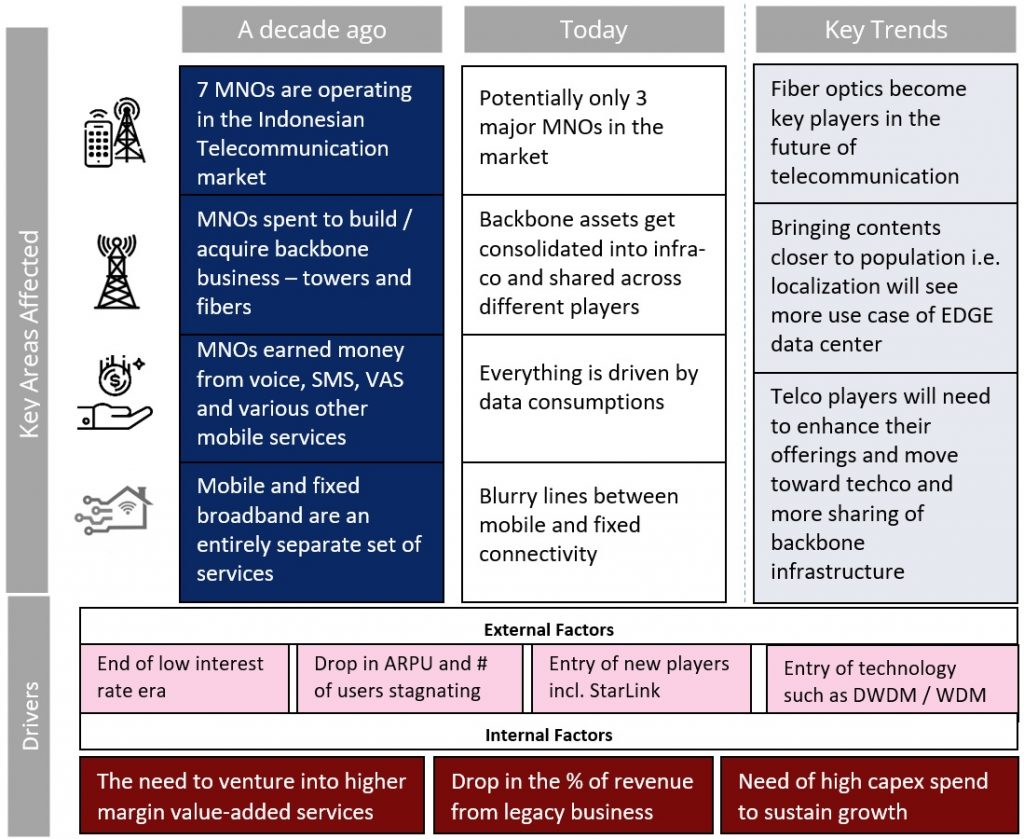

The Indonesian telecommunication sector has undergone a series of “evolutions” predominantly caused by digitalization, driven largely by increasing data consumption. This has triggered a set of “assets reorganization” activities marked by consolidations, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and divestments and the creation of infra-co.

Some of these activities are propelled by capital markets that have seen an increase in activity in the infrastructure private investment and higher cost of funds. More importantly, however, central to these is the convergence of telecommunication services that has now been largely driven by data connectivity and the demand for high-speed, high-quality and affordable communication.

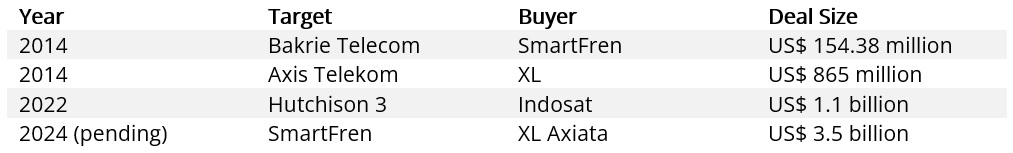

The Indonesian telecommunication sector has long been “mobile-centric,” primarily driven by mobile use as a more affordable and practical connectivity option. Before the wave of consolidation that occurred nearly a decade ago (sometime in 2015-16), there were 7 mobile network operators (MNOs) in Indonesia, namely Hutchison 3, XL Axiata, Indosat Ooredoo Hutchison, Sampoerna, Telkomsel, SmartFren and Bakrie Telecom.

Today, due to this wave of consolidation among these players (as detailed out in the table below) we are left with four key major MNOs. Soon, the country may only have three MNOs, as there is a potential merger between SmartFren and XL Axiata.

In addition to the wave of M&As among the MNOs, the Indonesian telecommunication sector has also witnessed a rise in divestments of telecommunication infrastructure assets, including telecommunication towers, data centers to fiber optics assets.

This trend it highlighted by the recent announced divestment Telkom Sigma, a subsidiary of Telkom Indonesia (a state-owned enterprise telecommunication company), and the proposed divestment of Indosat Ooredoo’s Fiber Optic and Marine Cable businesses.

This shift further underscores the ongoing reorganization of the Indonesian telecom sector.

Amidst these ongoing consolidations and divestments, we have also observed key emerging trends (discussed in further details below), including the rise of fixed-mobile convergence (FMC) in the Indonesian telecommunication landscape. This trend is exemplified by XL Axiata’s acquisition of Link Net, a major Indonesian fixed broadband player (initially owned by First Media, a subsidiary controlled by the Lippo Group and has been invested by a global PE, CVC), and the recent merger of Telkom’s subsidiaries – IndiHome (a fixed broadband service provider) and Telkomsel (one of the major MNO operators).

Underlying these corporate actions, is the significant increase in data consumption driven by digitalization and consumers’ contents consumption. This has made it strategically imperative for Indonesian telecommunication players to provide better quality and high-speed internet connections to grow their market share.

Specifically, in Indonesia, the fixed broadband communication segment has ample room to grow. The country currently has the lowest fixed-broadband penetration at less than 20%, significantly below Southeast Asia’s average of 40%, highlighting a significant opportunity for expansion and fiber optics investment in Indonesia. (DBS, 2023)

Furthermore, the services provided today are sub-standard, with average speeds that users typically get from the current fixed broadband internet service providers (ISPs) being only 31.42 Mbps, a far cry from the SEA internet speed of about 77.5 to 284.93 Mbps. (Ookla, Q2 2024)

This underscores the pressing need for improved broadband infrastructure and services in Indonesia, which could further drive the adoption of fixed-mobile convergence and accelerate 5G development to meet the growing demands of its digital population.

From our research and analysis, the bouts of divestment and M&As that happen in the Indonesian telecommunication market are mainly driven by several external and internal factors including but not limited to the following:

<External Factors>

1. The end of the low interest-rate era, bringing about an increase in the cost of funds, has raised the bar for return on invested capital.

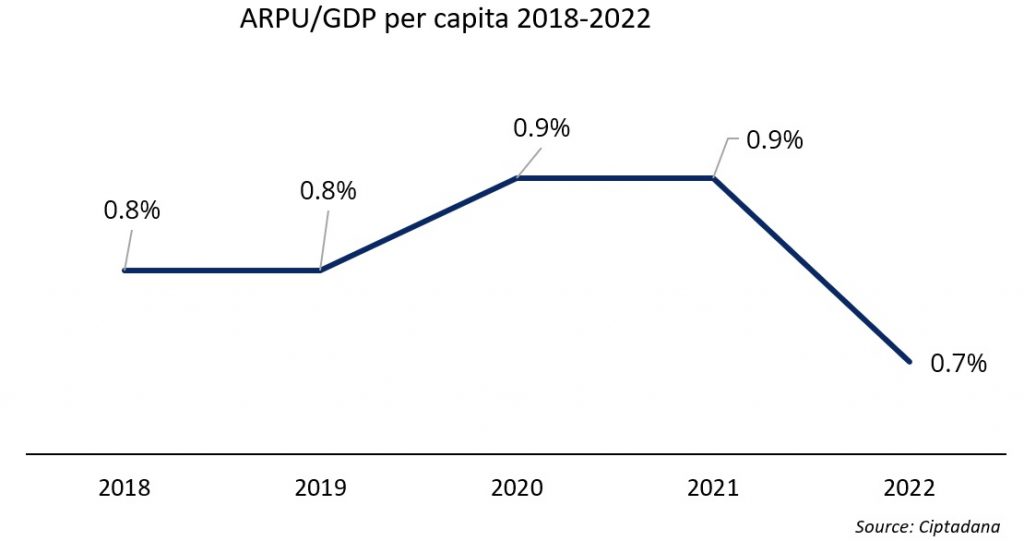

2. Heightened competition among the MNOs driving Average Rate per Users (ARPUs) downwards (shown by the decline in the ARPU/GDP Ratio in the chart below), while the number of subscribers remain stagnate.

3. Technological change, including the use of DWDM (Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing) / WDM (Wavelength Division Multiplexing) which essentially allows for a single fiber optic to cater for various data signals use has expanded the bandwidth capacity of a single fiber optic, making fiber optic use capacity more efficient.

4. The entry of new players in the market, especially with the recent entry of Starlink (the satellite internet entity belonging to Elon Musk), has intensified competition in the Indonesian telecommunication sector. Starlink offers an alternative way for consumers to access the internet; adding pressure to the already competitive landscape, though its reach is currently limited.

<Internal Factors>

1. The need for MNO players to seek new avenues for growth including providing higher value-added services, has become increasingly important.

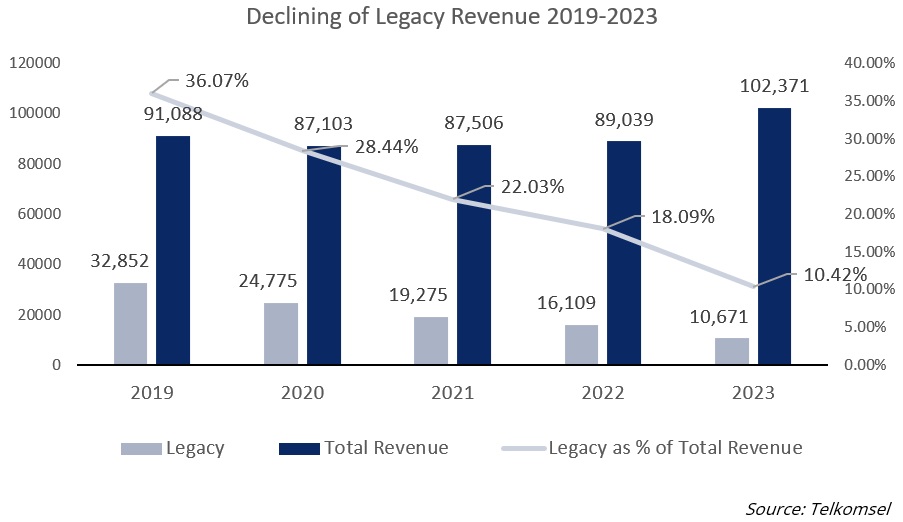

2. Adding to this is also the decline in legacy revenue streams (voice calls, SMS) for mobile companies, which now only provide a meager portion of the overall revenue (see below illustration on the proportion of legacy revenue to the total revenue of Telkomsel)

3. The high capital expenditure (capex) required to maintain competitiveness and/or to capture new markets has further driven the assets-reorganization. Combined with (1) and (2), this has triggered the slew of consolidation and divestment within the Indonesian telecommunication sector.

A confluence of these factors, coupled with the shift towards data-driven revenues, has resulted in the continuous shake up in the country’s telecommunications sector.

Driven by the rise of data consumptions and the strive for efficiency, the key trends in the telecommunication market in Indonesia will be mainly driven by the need to provide high quality communication more effectively i.e. higher quality and at lower price. Due to this reason, we likely to witness the key following trends:

1. Fiber optic investment in Indonesia will become crucial for the future of telecommunications, with FMC convergence and fiberization enabling high-quality, affordable internet

Driven by increasing need of data, fiber optic, with its ability to channel vast amounts of data efficiently and effectively and with its already proven technology, has been the clear winner. In addition, the use of DWDM and WDM technologies is a breakthrough that has increased the amount of bandwidth capacity that can be channeled by a single fiber optic network.

Adding to that, fiberization – which is basically connecting tower to the fiber optic cable becomes the key for 5G development in Indonesia. We have seen this done in major markets such as India and China. This also means there is a convergence whereby fixed broadband will generally empower the telecom tower. Hence Fiber optic is a clear winner of this transition and evolution.

2. EDGE Data Center will provide further content localization

With increased content consumption, placing content closer to users to reduce latency has become ever more important. Edge data centers (EDGE), which is essentially smaller sized data center closer to the population of end users and utilization of content delivery network (CDN), which is essentially network of servers with the goal of delivering content quickly, cheaply, reliably, and securely as possible, are crucial in this “localization” effort.

3. Telecommunication companies will evolve to become “techcos”, whereas infrastructure companies will focus on deepening their infrastructure play, creating a more scalable back-end sharing economy

With the creation of “infra-co” companies, separating infrastructure ownership from operations, is supported by the rise of infrastructure investors, particularly infrastructure private equity funds, seeking exposure to digital infrastructure.

Whilst operating-co will focus on providing more value-added, higher return and technological based servicing. We can already see this happening in developed markets such as Singapore, where Singtel and StarHub have made acquisitions in the enterprise services sector to expand their offerings in this area.

We in IGPI Singapore have been active in the telecommunication sector in the region, working with not only key telecommunication clients across various spectrums, but also with various infrastructure and non-infrastructure investors who are looking into investing and getting exposure into the SEA telecommunication market. We are happy to discuss and assist you on your strategy and investment matters.

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Mr. Erwin Thio is the Senior Manager of IGPI Singapore. His areas of expertise are in M&A deal management (both buy-side and sell-side), deal structuring, valuation and commercial due diligence, market analysis, and project management. He has also spent several years working within the investment and fund management (particularly for Real Estate Private Equity Funds) division of major developers such as Mapletree, Lendlease, Savills IM, and CFLD, where he helped with deal execution and origination, capital raising, fund creation/ development, and management.

Mr. Nicholas Quek is an Associate of IGPI Singapore. He graduated from Singapore Management University with a Bachelor of Business Management, majoring in Finance. During his time in university, he gained internship experience at OCBC bank where he took on a compliance role responsible for AML. He was also a Teaching Assistant for Financial Markets and Investments, and a Research Assistant for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). In his final year, he embarked on an experiential learning course where he formulated strategies to increase e-commerce sales for an MNC.

Mr. Darren Hardisurjo is an Intern at IGPI Singapore (August 2024 – October 2024).

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

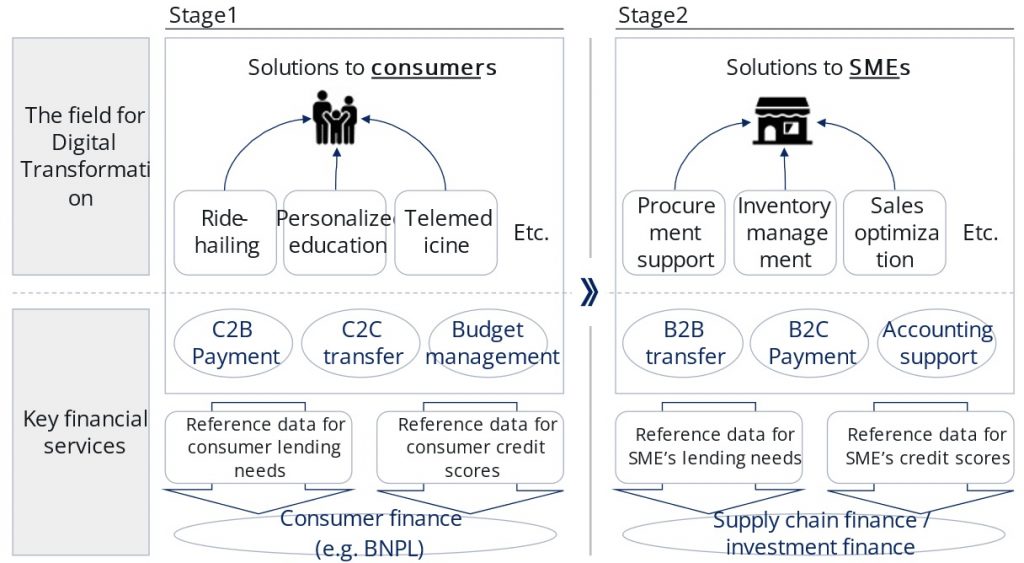

In the financial business market of Southeast Asia, B2B financial services integrated with operational DX for SMEs will be the key.

This article delves into the author’s perspective that the frontier of Fintech in the Southeast Asian market is shifting from the B2C domain to the B2B domain based on the latest Fintech trends.

So, what exactly is Fintech? While Fintech can be defined in various ways across different media sources, this article defines it as ‘financial solutions’ that meet at least one of the following two conditions:

1. Using digital technology to provide financial services to a broader user base than previously possible.

2. Using digital technology to increase the value of financial services provided to users.

One fundamental aspect to understand is that “financial services rarely stand alone.” This is because financial services typically involve the movement of money, which is accompanied by the movement of related information, such as the product or service being paid for, collateral assets, or credit involved in a loan. Since “money isn’t free,” the evolution of Fintech services is inevitably influenced by the degree of digitization of peripheral services. Thus, it is safe to say that advancements in Southeast Asia FinTech are closely linked to how digital transformation impacts the broader financial ecosystem.

Since the 2010s, the digital transformation in Southeast Asia has rapidly advanced in the B2C domain, reaching levels of convenience that surpass those in some advanced countries like Japan and Europe, particularly in sectors such as mobility, education, and healthcare. Examples of this Southeast Asian Fintech evolution include lifestyle support platforms like Grab (Singapore) and Gojek (Indonesia), which initially began as ride-hailing services. Additionally, personalized online education solutions like Geniebook (Indonesia), and online medical consultation solutions through platforms like Alodokter (Indonesia) highlight the advancements in ASEAN Fintech.

In the ASEAN Fintech landscape, digital services such as C2B/C2C payments and budget management have emerged alongside these innovations. Additionally, the data obtained from these services is used to assess consumer credit scores and lending needs, leading to the provision of consumer finance services like BNPL (Buy Now, Pay Later).

However, consumer financial services, particularly payments and BNPL, often face intense competition, resulting in persistently high customer acquisition costs. For example, Atome, a BNPL service provider based in Singapore, announced in May 2023 that it would cease all operations in Vietnam more than a year after entering the market.

Conversely, the digitization of operations for SMEs, which are the backbone of the Southeast Asian economy, remains sluggish, and productivity continues to be low. For instance, the situation in Thailand, a relatively advanced region in Southeast Asia, is as follows:

Agriculture:

| ✓ | Despite 47% of Thailand’s land and 33% of its labor force being engaged in agriculture, agricultural production accounts for only 8-11% of GDP. | |

| ✓ | 30% of agricultural households carry debt exceeding the average annual agricultural income per capita, with 10% carrying debt three times that amount. | |

| ✓ | Total rice production has decreased from 38 million tons in 2012 to 22 million tons in 2022. | |

| ✓ | Only 23% of farmers use ICT-related tools in their operations. |

Logistics:

| ✓ | B2B deliveries from region to region often use point-to-point routes, resulting in low loading efficiency for LTL (less than truckload) shipments. | |

| ✓ | 46% of annual freight transport involves empty backhauls. | |

| ✓ | In 2020, Thailand’s domestic logistics costs accounted for 14% of GDP, higher than the Asia-Pacific average (12.9%) and many other regions worldwide. |

Given this situation, some financial solution providers focus not solely on financial issues but also on supporting the productivity enhancement of SME operations. They capture financial needs and monetize by providing tailored financial solutions. For example:

| ✓ | CrediBook (Indonesia) assists MSMEs and mom & pop stores with digitizing operations and securing financing by offering a bookkeeping and reporting SaaS tool, which simplifies the process of applying for micro-financing from financial institutions easily. | |

| ✓ | Kilimo Finance (Vietnam) operates through a digital marketplace, allowing Vietnamese farmers to purchase farm inputs (e.g., seeds, crop protection, and equipment) through a wide network of suppliers. It also seeks to connect small and medium-scale agriculture players to commercial banks to enable access to formal credit through its automated credit scoring and loan origination software. |

In the future, Fintech players who contribute to improving SME productivity using digital technology and, through this process, meet customers’ financial needs while leveraging credit score-related data to provide financial solutions will occupy an essential position in the Southeast Asian market.

Considering this Southeast Asian Fintech trend, B2B operation DX technology companies might use the data they acquire to offer additional financial services, either directly through earning interest income or through partnerships with financial institutions. Conversely, existing financial institutions can acquire new customers by partnering with, investing in, or acquiring technology startups that drive digital transformation in adjacent areas of finance in Southeast Asia. They can also improve credit scoring accuracy by utilizing income statement-related information such as sales and balance sheet-related information such as accounts payable obtained through operational support, enabling risk-mitigated financing.

Particularly in emerging markets, SME financing is a significant revenue expansion opportunity for both parties due to its higher risk and higher interest rates.

IGPI offers business model hypothesis construction and verification, partnering support, and M&A support during the execution phase, not only for financial institutions but also for technology companies. If IGPI can be of assistance, please contact us through our website.

Mr. Tadasuke Noguchi is a Manager at IGPI Singapore. Before joining IGPI, Tadasuke worked in an IT company and a think tank in Japan, where he engaged in consulting projects such as new business development in various industries: automotive, logistics, retail, finance, etc. He has experience in hands-on new business development while on loan to Toyota Motor Corporation’s R&D department. In IGPI, He mostly focuses on consulting projects such as market entry/expansion in the ASEAN market, M&A advisory, and the formulation of long-term visions. Tadasuke graduated from the University of Tokyo with a B.A. in Language and Culture and acquired a certification from the Graduate School of Public Policy of The National University of Singapore. He enjoys traveling and has visited around 50 countries.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

There is an increasing momentum for promoting decarbonization in ASEAN, which was originally said to be lagging compared with other regions.

Regarding the systems to promote the development of decarbonization projects, the study and implementation of carbon pricing are in full swing. In enforcing enforceable carbon pricing, Singapore was ahead of other ASEAN countries in implementing a carbon tax system in 2019. Indonesia has followed suit with an intensity-based Emissions Trading System (ETS) targeting coal-fired power generation. Many other ASEAN countries have also announced their consideration of the introduction of carbon taxes and ETS.

Regarding project development, large-scale project development is accelerating. For example, in Malaysia, the Final Investment Decision (FID) of a large Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) project (Kasawari) has been completed, and the project has moved into the construction phase. The scale of the project is expected to reach 3 million tons of CO2 per year. Considering that the size of one of the largest existing CCS projects in Japan, the Tomakomai CCS Demonstration Project, is equivalent to 200,000 tons per year, it could be said that the size of the Kasawari CCS Project is quite remarkable.

The background for the acceleration of decarbonization projects in ASEAN stems from international community pressure, driving both the public and private sectors of ASEAN to commit to achieving decarbonization targets.

In the public sector, this commitment is exemplified by a series of net-zero declarations by ASEAN countries, starting with Indonesia’s net-zero declaration by 2060 in June 2021, complemented by initiatives such as Repsol SA’s 2020 Sustainability Plan for Indonesia.

In the private sector, it is also due to the increasing pressure from large global companies to achieve decarbonization of their global supply chains.

Beyond these factors, it is also important to note that in terms of project development resources, ASEAN boasts abundant natural resources. For example, forests account for the majority of voluntary credit issuance in ASEAN. This is backed by abundant forest resources, led by Indonesia, which has the third-largest forested land in the world[1].

In addition, offshore wind power, which has been attracting attention in recent years as a trump card for the diffusion of renewable energy, shows promising potential in Vietnam and the Philippines despite the limited number of countries and areas where it can be developed. Notably, there is a high potential for “bottom-fixed” type wind energy in the two countries, which is superior to “floating” type in terms of feasibility, and many foreign companies are exploring opportunities in Vietnam for upcoming large-scale projects.

As mentioned above, ASEAN is a region where the development of decarbonization projects is progressing, with a background of abundant natural resources.

One of the characteristics of project development in ASEAN is the deep involvement of foreign companies in the consortium. The background to this is the need for foreign companies to fill a role that cannot be filled by their own countries, both in terms of funding and technology. Notably, the contribution of Japanese companies is extremely high.

In fact, the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM), which began operating in 2015, and the AZEC initiative, which was proposed in January 2022, positions ASEAN to be the core partner and aim to share the fruits of decarbonization by providing Japan’s excellent decarbonization technologies with ASEAN companies. Against the backdrop, it is expected that “decarbonization” will be an opportunity to strengthen ties between Japan and ASEAN.

IGPI Singapore has experience supporting clients with market research and developing market entry strategies in a wide range of decarbonization-related topics in ASEAN.

Below is a sample of areas where we have assisted in the past.

◆ Renewable energy (solar, wind (including offshore), biomass, geothermal, hydro)

◆ Hydrogen and ammonia

◆ Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS)

◆ VPP/DR

◆ Carbon credits

◆ Green finance

To find out more about how IGPI can provide Japanese consulting support for businesses in Singapore and the region, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

[1] Renature “Insights on Indonesia” (2020)

Mr. Tatsushi Sasakura is a Senior Manager of IGPI Singapore. Tatsushi has worked at Mizuho Bank and Deloitte Tohmatsu Financial Advisory (DTFA) in Japan. At DTFA, he belonged to the Corporate Strategy team, specializing in business strategy planning, M&A advisory, and business due diligence. He was also engaged in crisis management, supporting clients to tackle emergencies. He has profound experience in the energy, consumer, and financial industries. He covered a wide range of clients, including Private Equity Funds and large-sized companies. Tatsushi graduated from Waseda University with a B.A. in International Political Science and Economy.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

Although the EV penetration rate (EV share of new car sales) in the U.S. in 2023 grew year-on-year to approximately 7.6% due to incentives such as tax credits and regulations, it fell significantly short of expectations. Amid slowing demand growth, the EV market leader Tesla revealed a 55% y-o-y decline in final profits in its January-March 2024 financial results, due in part to increased competition and lower sales in key markets.

The Chinese EV industry, which grew rapidly owing to government subsidies, has witnessed a drop in the number of registered EV manufacturers from about 500 in 2019 to less than half that number today due to the economic slowdown and intensified competition. The number of manufacturers discontinuing EV production is expected to increase in the future, with a growing trend of “EV graveyards” in China as large numbers of EVs are left abandoned by those who have withdrawn from the market.

Market oversaturation and declining purchasing interest — stemming from concerns about driving distance limitations, unaffordable prices, and insufficient recharging infrastructure — have contributed to these situations.

Enthusiasm for ESG is also waning globally. Particularly in Europe, there is growing criticism surrounding the quality of ESG reporting by companies, marking a trend towards more formal initiatives. A 2021 survey raised concerns that many companies are overstating their ESG activities, making it difficult for investors to discern true commitment to sustainability. Additionally, the credibility of ESG investments may face growing scrutiny if there are no tangible improvements in environmental protection.

This evolving landscape presents ASEAN as a beacon of innovation and adaptability, distinguishing it from global trends and highlighting its unique position on the world stage.

In Southeast Asia, however, there are no signs of such stagnation.

In Vietnam, several of VinHomes’ smart cities are promoting green projects to transition entirely to electric vehicles. From the expansion of electric bus routes by VinBus to the provision of EV cab services by Green and Smart Mobility (GSM), Vingroup has adopted a strategy of not only selling EVs to consumers, but also replacing low-quality public transportation and cabs with EVs to rapidly increase EV penetration. As a result of these efforts, Vingroup was awarded the AIBP 2023 ASEAN Tech for ESG Award, which recognizes sustainable initiatives with the use of digital tools and innovative technologies.

In Laos, where approximately 1,300 EVs were registered as of 2022, government support and international partnerships contributed to the sale of approximately 2,600 EVs in 2023 alone. In November of the same year, the aforementioned Vietnam GSM launched an EV cab service in the capital city of Vientiane as a first step in planned business-led strategic EV rollouts. The low prevalence of automobiles, severe gasoline shortages due to global oil price surges and low electricity costs through the utilization of abundant renewable energy resources have become major driving forces behind these initiatives.

EVs are also becoming more modular and require far fewer parts than gasoline-powered vehicles. In expanding EV sales, meeting local needs is more critical than pursuing global growth, and whether a country is suitable for EVs depends largely on its energy mix.

Innovation is often referred to as “creative destruction” and is considered to involve the destruction of what existed before and the creation of something new. In fact, in Japan’s regional cities, privately owned stores are disappearing, being replaced by restaurant chains and convenience store chains, which has resulted in the loss of the local communities that once thrived.

Yet advances in digital technology have, for example, revitalized rather than destroyed traditional, privately owned mom-and-pop stores in Southeast Asia. Consumers can order products via a smartphone app and a rider will deliver these from stores to homes within 30 minutes. Similarly, stores can replenish stocks through B2B e-commerce when necessary at the touch of a screen. Without destructive disruption, smartphone application technology has organically connected retailers and consumers.

Innovation in these ASEAN countries is driven by attempts to create new frameworks rather than being constrained by existing ones. New technologies and strategies are actively employed to solve region-specific challenges without relying on existing approaches.

This digital revolution has significantly expanded the range of what can be accomplished by individuals. Anyone can distribute video content around the world, and startups can manufacture electric cars. In such an era, it is imperative to provide optimal services to the localized market based on localized needs and context rather than to the entire world. Innovation, achieved through the utilization of existing technologies and services to expand the capabilities of people and organizations, represents “creative integration” rather than “creative destruction” and holds the key to achieving a sustainable society.

In an era where providing services tailored to the specific needs of each region proves more effective than offering generic global solutions, success or failure will hinge on how quickly a company adapts to changes in the environment and how flexibly it responds — while fundamental structural changes may be necessary at times, much can be accomplished even with simple tweaks in policies. A flexible response to the changing environment is enabled by management setting an abstract, conceptual direction, such as a Purpose, while frontline personnel consider the concrete specifics of “to whom,” “what,” and “how” before executing their actions. In doing so, agility will also be achieved by empowering the frontline with the requisite authority and resources to execute and deliver.

Furthermore, understanding regional circumstances and maintaining local networks, including partnerships with local conglomerates and startups, is crucial to swiftly detecting environmental changes, particularly in the ASEAN region. The development of digital technology has indeed greatly expanded the scope of what individuals can achieve. However, challenges that cannot be tackled alone or by a single company remain, and partnerships are a crucial driving force to overcome these barriers and propel innovation forward. Companies have to understand their strengths, utilize available resources to secure the capabilities necessary to maximize the value of said strengths and create new value through collaborations around the world.

IGPI assists global companies, local conglomerates, and governments in fostering innovation across Southeast Asia, creating business models that harness each region’s unique potential, and developing new markets through management consulting and strategic investments. By continuing to support sustainable development and innovative initiatives in the regions, we provide valuable insights for companies and investors around the world.

To find out more about how IGPI can provide consulting support for businesses, browse through our insight articles or get in contact with us.

Mr. Kohki Sakata is CEO of IGPI Singapore. After joining Cap Gemini and Coca-Cola, Kohki joined Revamp Corporation, where he managed projects on global expansion and turnaround in various sectors, including F&B, healthcare, retail, IT, etc. Since joining IGPI, Kohki has managed projects mainly on global expansion and cross-border M&A in various sectors such as logistics, IT, telecom, retail, etc. In addition to his broad experience in implementing solutions developed in Western countries, he has developed multiple methods to turn around Asian companies with a focus on setting a clear vision and employee empowerment. He has proven the practicality of these methods by turning around Asian companies not only as an advisor but also as senior management. He graduated from Waseda University Department of Political Science and Economics and IE Business School.

Industrial Growth Platform Inc. (IGPI) is a Japan-rooted premium management consulting & investment firm headquartered in Tokyo with offices in Osaka, Singapore, Hanoi, Shanghai & Melbourne. IGPI was established in 2007 by former members of Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), a USD 100 billion sovereign wealth fund focusing on turnaround projects in Japan. IGPI has 13 institutional investors, including Nomura Holdings, SMBC, KDDI, Recruit & Sumitomo Corporation, to name a few. IGPI has vast experience supporting Fortune 500s, government. agencies, universities, SMEs, and funded startups across Asia and beyond for their strategic business needs and hands-on support across a wide variety of industries. IGPI group has approximately 7,500 employees on a consolidated basis.

* This material is intended merely for reference purposes based on our experience and is not intended to be comprehensive and does not constitute as advice. Information contained in this material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but IGPI does not represent or warrant the quality, completeness, and accuracy of such information. All rights reserved by IGPI.

This article outlines the potential of the cultivated meat industry, discusses the primary barriers, and how IGPI’s business consulting services can help clients in Singapore and beyond.

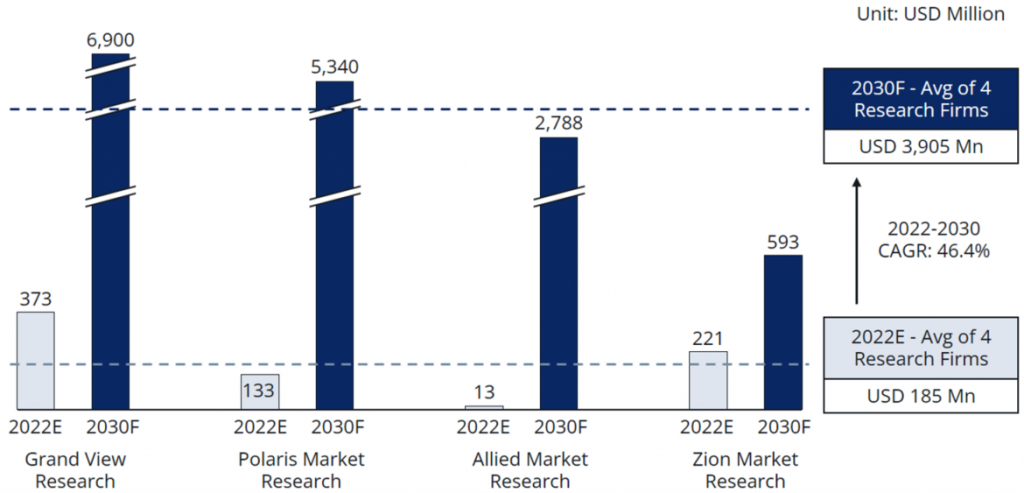

Figure 1; Market Size Projection of Cultivated Meat Industry[1]

Experts from various research firms have reached a consensus on the promising trajectory of the cultivated meat industry, anticipating substantial growth between 2022 and 2030. Projections indicate a remarkable increase from an average of $185 million in 2022 to an impressive $3,905 million in 2030[2], reflecting a significant compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 46.4%. The rapid expansion in the market is attributed to the advantages offered by cultivated meat, such as promoting a healthier diet, environmental sustainability, and animal welfare[3]. The potential of cultivated meat to address key problems in the conventional meat industry provides it with the opportunity to become an alternative in a space that is worth USD 1.4 trillion in market size in 2023.